Why I Vanished from Social Media

I wish I could say there was only one reason. But there was definitely a primary reason. The last two months have been a little rough for my family. My little sister had a major stroke. For those of you who've had a loved one go through this you'll understand perfectly what I mean. It's sudden, unexpected, and unfortunately my sister didn't make it to the hospital in time to get the medication that would have saved her from the more severe damage. So there we were: a family in turmoil having to make major decisions regarding my sister's life.

Truly, social media had become habitual chaos. Posting, commenting, liking, sharing across four--sometimes five--platforms can be a lot. When real life happens, suddenly it can appear to be a little absurd. With the challenges of new circumstances, clicking on a social media icon was too difficult. My little sister's life was forever altered, and there was a window when we weren't sure if she would survive. So eventually, I went onto all my social media sites and just deleted them. One after the other and in a matter of a seconds they were all gone. And there was something empowering about that moment. I knew what mattered most and I was going to give it my full attention.

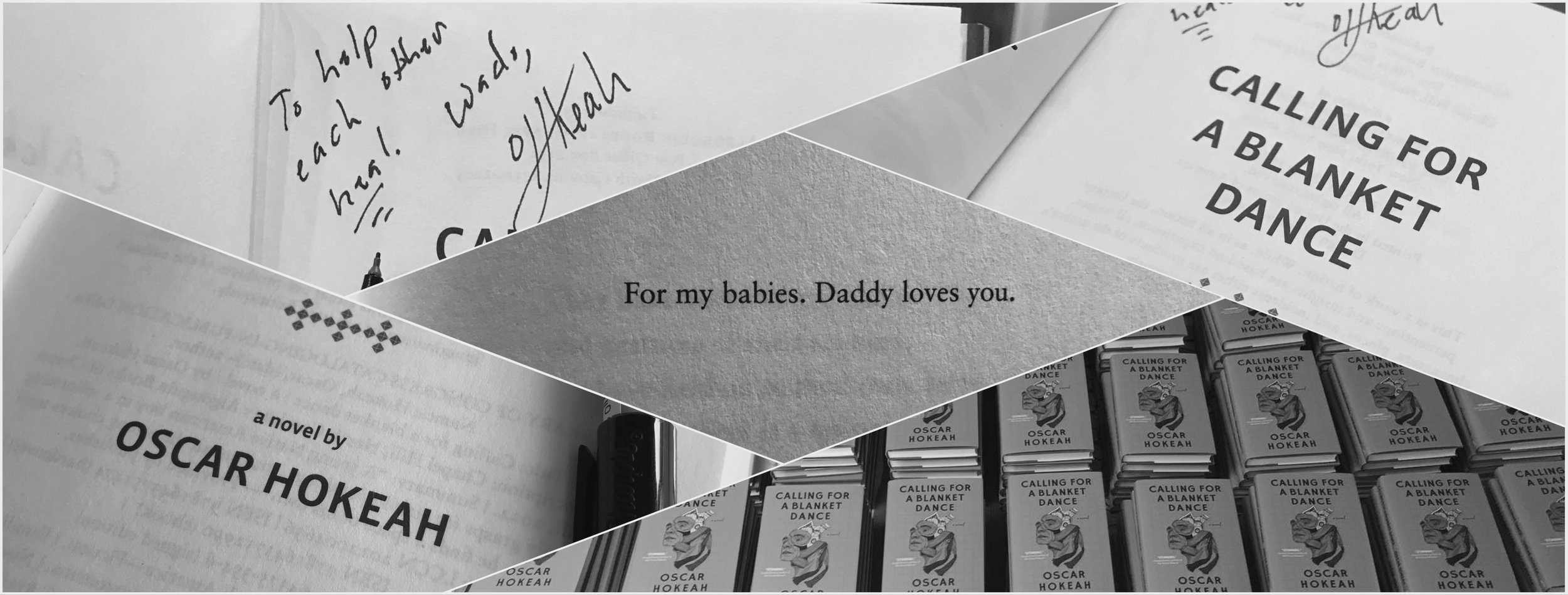

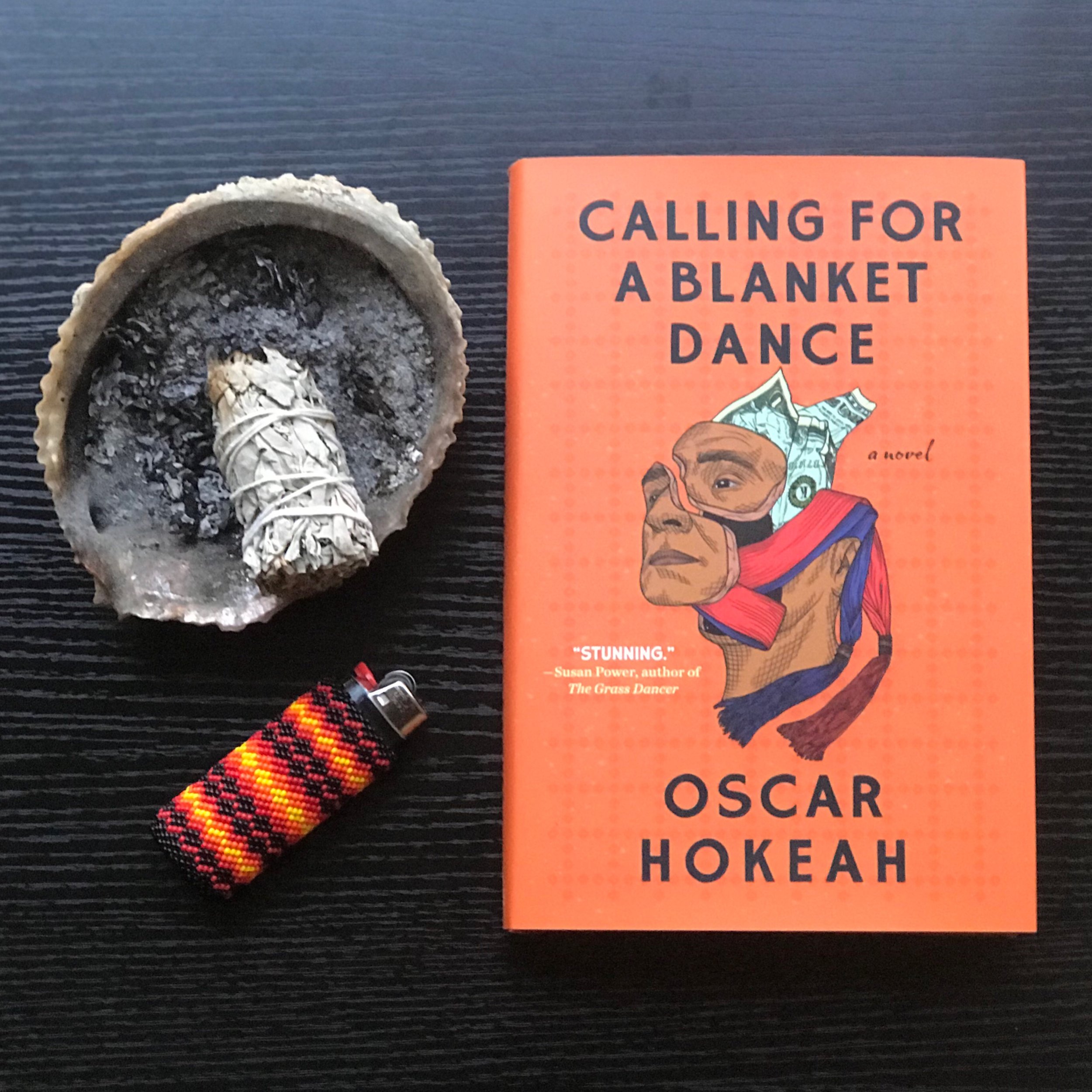

There was a part of me that felt a little guilty. I had released my debut novel in late July and had been plugging away on social media to promote the book. I met many great folks. Sometimes I wished I had that back again. The playful comments and genuine connections. There are a ton of kind and generous people out there. Right now my days are filled with juggling my kids' needs, helping with my little sister, and continuing to serve in Indian Child Welfare. We just finished Cherokee Nation's Angel Project where we gave Christmas gifts to 2,800 Cherokee children in need. We made Christmas a little brighter for some of our most impoverished citizens. I also got to spend quality time with my daughters, and worked with my little sister to help her speak again. It's been busy and trying in profound ways.

I'm grateful, and I've been good about being grateful, but maybe I'm a little more grateful these days. Maybe sometime in the future I'll start my social media back up again. If a new normal ever sets in. For the time being, I'll be posting here on my blog. It's much more straight forward and easy to engage with. Right now I need to keep my life simple to get through.

In Defense of Peripheral Narration: Fitzgerald Vs Hokeah in a Battle of Class, POV, and Power

Have you heard of a book called The Great Gatsby? It's written by F. Scott Fitzgerald. Most folks read it in high school. I didn't make it to high school (the last grade I completed was the sixth grade) so I didn't read it until I was an adult (after I went on to obtain a Master's Degree). If you remember, the novel is told by a character, Nick Carraway, about another character, Jay Gatsby. The reason I'm bringing up this particular book is two fold: (1) It's well known, and (2) it's a popular example of peripheral narration, where one character tells the story of another character. Don't worry this is not a rehearsal of Fitzgerald's novel. Instead it's an allusion to mine.

If I were to make a comparison between The Great Gatsby and my debut novel, Calling for a Blanket Dance, I'd argue it takes peripheral narration and amplifies it. Why? I enhance it with polyvocality. Both books are short reads that pack a big punch, yes. But we, Fitzgerald and I, operate from opposite ends of the class spectrum. As you probably know, The Great Gatsby is about the wealthy and critiques the American Dream by showcasing the underbelly of the uber-rich, where Calling for a Blanket Dance is an homage to the working class, who aren't trying to stratify a system but simply want to live without becoming victims to a movable standard. The Great Gatsby is to the wealthy what Calling for a Blanket Dance is to the working poor.

“There are only the pursued, the pursuing, the busy and the tired.” ― F. Scott Fitzgerald,The Great Gatsby

All that aside, let's think about the periphery. If we were in a creative writing class, I'd probably give you reasons why an author, such as myself and "old boy" Fitzgerald, would employ it as a technique. These reasons tend to be somewhat obvious, like the main character might have a secret, she or he might die during the course of the novel, they could be unlikable and therefore not relatable, and/or each story might be more important to the narrator(s) than it is to the main character. But this is not a creative writing class so I'll not go on about those.

What I will address is the richness of peripheral narration when doubly executed with polyvocality. What happens when 11 different people tell a story about you? If they were coworkers, we'd probably get the down and dirty about your shady-ass past and how you're not as angelic as you might think you are. If it's your family, then we'll get something a little more diverse, a little softness to go along with the prickly. Bittersweet, if you will. And I'll argue here that we'd get more depth about you as a person from your family than we would from you. Using peripheral narration mixed with polyvocality gives readers a much richer and deeper understanding of a main character.

“Let us learn to show our friendship for a man when he is alive and not after he is dead.” ― F. Scott Fitzgerald, The Great Gatsby

Ultimately, it gives us more than the typical drama triangle (villain, victim, hero). Instead we move away from Western traditions in literature and step a little closer toward Indigenous ideology, like shaping an entire novel on traditional Kiowa and Comanche customs (say a Blanket Dance, maybe). Here the community has agency--not the individual--where a collective center from a tribally specific and historically targeted community wrap around each other in support, healing, and decolonization. Where we acknowledge how we are shaped by the people who love us the hardest. Moreover, where a chorus of voices sing in rhythm with a single thundering drum, reverberating out and across the planet to announce: our power is back.

Digesting Fragments as Memories: CALLING FOR A BLANKET DANCE

Let me ask you a simple question: What was a significant event in your life? Moreover, how did it impact you, change you, make you into the person you are? What I like most about this question is how it immediately takes us deep into memory. Suddenly a series of memories flood our minds and we rifle through each to determine which might be the most impactful. Now let me switch it on you. What if I asked each of your relatives about the most significant event in your life?

Suddenly, we might have multiple stories. Your grandmother might tell a different story than your grandfather. What about your parents? Your spouse? Your siblings? Your cousins, aunts, uncles? Now we have an entire chorus, a symphony if you will. And in this symphony the music is an ensemble of memory.

“It's enough for me to be sure that you and I exist at this moment.” ― Gabriel García Márquez

One could argue we primarily exist by memory. The memories others have of us. The memories we carry about ourselves. Each moment we share in real time can only be processed in memory. Does this mean there is no here and now? Is memory the only form of existence?

Before I carry on too much longer with all these questions let me say here that my debut novel, CALLING FOR A BLANKET DANCE, allows readers to consider these very questions. The structure of the novel is told by 12 narrators. The main character is Ever Geimausaddle. Each chapter is told by a different family member. We start with his grandmother, Lena, and then move onto his grandfather, Vincent, followed by his uncle, Hayes, and so on and so forth, going through aunties, uncles, cousins, and his sister. Then in the final chapter we hear from Ever himself.

Where the aspect of memory comes into play is the time span between each chapter. Lena tells us a story about when Ever was an infant, while Vincent tells us a story about when his grandson was five years old. Then his uncle follows with one from when Ever was 10 years old. The chapters hop three to five years at a time, and does so into his adulthood, ending when Ever is in his early 30s.

Why would I do this? What's the purpose of spanning so much time between each chapter?

The simple answer: memory. How does our memory work? When I ask you about a significant event, your mind searches for moments in time. It doesn't run in a linear fashion without any breaks from the moment you were born until this very moment. So this begs a bigger question: Do our lives only exist in fragments? If we are simply constructs of memory, how much say do we have in the constructs of our own identity? To my mother, I'm a son, but to my best friend, I'm a brother. In order to truly see into the depths of who we truly are, don't we depend on the memories of others?

“He was still too young to know that the heart's memory eliminates the bad and magnifies the good, and that thanks to this artifice we manage to endure the burden of the past.” ― Gabriel García Márquez

Let the spaces in between each chapter jar you, let them force you into new spaces, let them make you imagine a new version of time--maybe a more honest version of time. Not only will you truly see Ever Geimausaddle as a loving and flawed human being, but you'll forgive yourself for being one too.

“Please — consider me a dream.” ― Franz Kafka

(The image was borrowed from flickr.com)

Gritty Conversational: A Contemporary Native American Voice to Combat Erasure

So I was sitting in a classroom at the University of Oklahoma. This was about a decade ago. I was in my master's program and it was a special topics course on heteronormativity in American culture. We were discussing James Baldwin's work, and the professor said, "I love Baldwin's writing and I don't know how he does it." Then he looked at me. We locked eyes for a moment. I'm the only one in this MA program who has a BFA in Creative Writing. I immediately thought, I know how he does it. But before I had a chance to respond, he quickly stated, "And I don't want to know," as if he knew I was about to break the spell.

What we writers do can appear to have a magical quality. And after you've gone through a BFA or MFA program you learn all the craft techniques, like how to capture a plot, who to draw as a character, and, moreover, what voice to use to cast your spell.

This weekend I've thought a lot about my debut novel and varying elements within it, like structure, theme, character, and voice. I could talk for days on each of these, but often it's the latter that stumps most. Voice is elusive. While I thought about how the theme of my novel ties into the title, wanting to connect this for readers who might ask or for readers who might be interested in the larger thematics, but what I landed on was voice.

I thought about some of my favorite authors and how their writing styles are described. Words like conversational, gothic, magical, rural, and emotional kept popping up. Then I reflected on my own writing style or voice and came to each of the descriptors above. Often the writers we adore blend into the writer we become. And I landed most often on a single phrase: gritty conversational.

I'm a regionalist writer interested in capturing intertribal, multicultural, and transnational dynamics of my home communities--Tahlequah and Lawton, Oklahoma. As an engine for my writing, I'm most interested in realism. And the reason has to do with the romantical perspective people have about Natives. There seems to be this drive to reduce Natives to ahistorical tragic figures or overtly spiritual beings, like we're not contemporary people living and struggling inside a postmodern society.

Trying to convince people that we're human is a fulltime job in itself. Many of the depictions of Native peoples are of the above situations, and when both ahistorical tragedy and spirituality are mixed it becomes a much more harmful version of erasure. It's the modern version of the Pristine Myth, where people want to believe we Natives are no longer here, that Natives don't truly exist. We are either other worldly or in the past.

So I end up writing the grittiest version of who we are, because this captures Native people as being like everyone else. We work, care for our kids, do idiotic shit, love hard, fail even harder, and triumph in the last minute. But simply saying those words doesn't do enough. Readers need the emotional ride to truly understand, to truly grasp how we fit into the fabric of a global community.

This morning, I thought about my professor from back in the day, who wanted to be spellbound, and I couldn't help but think about how many readers want the Pristine Myth, they want Natives to be some sort of bizarre ahistorical tragedy comeback from the dead to save their souls. So weaving these stories with my "gritty conversational" style is a magic meant to wake readers from what they believe is a beautiful dream--but to us Natives it's the transformed but continued nightmare that began 530 years ago.

The Aftermath of the Final Draft: Novels

So I'm about to use this post as catharsis. I've done something tremendous. So momentous that it's a little unsettling. Or maybe I've made it unsettling by overthinking. But I can't help but wonder if this is a normal part of the process once a writer has submitted the final draft of her novel to an editor.

I received edits from my editor a couple months ago, and I immediately went into hiding. All my thoughts were focused on one thing: revise. The closer I came to the deadline, the more intense the focus became. Sure I asked for a couple extension. My book is my baby and I wanted to hold onto it for as long as I could. Then it came to the last extension. The book needed to move toward production, and I had squeezed out every possible moment.

“There is a ruthlessness to the creative act. It often involves a betrayal of the status quo.” ― Alan Watt

Then on Tuesday morning it happened. It was the first day of June. The year was 2021. Just after Labor Day weekend. Rain had been falling off and on for days. Tahlequah, Oklahoma had just left behind it's harshest storms and true summer sun was within grasp. That morning I woke and said, "I'm ready to let the book go. It's time." I had spent all my mental energy on this day.

Fast forward about two hours, I typed a short note in an email, clicked attach, and then the last step: send. It was done. The final manuscript shot into cyberspace and landed inside the inbox of my editor and agent. Congratulatory emails returned. My final draft was officially submitted.

What happened next was a complete shock. I thought I'd be relieved and excited and would run around the office giving everyone high fives and people would take me out for a meal and some drinks and I'd fly in a jet to Peru and dine with elite writers from multiple hemispheres. But no. That did not happen.

What did happen? I was instantly depressed. I was suddenly sad. I was oddly withdrawn.

I thought, What's going on with me? This can't be normal.

“Writing is a struggle against silence.” ― Carlos Fuentes

I had spent so much time focused on the revisions and the moment I'd click send that I had not even thought about what was to come afterwards.

The only thing I can equate it to is the same feeling I had when my three adult children moved out. Like the time when my oldest son and I had breakfast one day. An innocent enough meal. But it was the first meal we had together where he'd leave in his car to his apartment and I'd leave in my car to go to my home. He wasn't coming home with me. He was no longer a child, and what we once had would never be the same again.

I suddenly realized I was mourning the loss of my book. I'd never delve into its pages the same way again. I'd reread the pages at some point in the future, but it'd never be the same. I no longer had anymore influence on it's words, it's chapters, it's characters. Now they had to do everything thing on their own.

This was the moment I realized why I kept asking for extensions. Certainly, there were tweaks to be made, but I couldn't deny there was this sense of trying to hold on, trying to have one more moment, one more memory before it all changed. Even if I didn't consciously realize it. I was holding on as long as I could.

It's scary when your child steps into the big, bright world. There are so many obstacles and pitfalls. But you can't be there for everything. To a certain extent, your baby needs to make mistakes--no matter how young you perceive him to be.

“Some part of me knew from the first that what I wanted was not reality but myth.” ― Stephen King

I've been working on this novel for a very long time. The oldest story in the novel was written in 2008. That's 14 years ago! By the time my book hits the market, it'll have been 15 years from the moment the oldest story was written. It took one and a half decades for this novel-in-stories to reach maturity. That in itself is a unique story to share.

But I have to move forward. I've popped open my other two novels and added a sentence in one, reread a few pages in the other, and stared at the line of chapters running down my flash drive. I want to be ready to move forward. But I might have to give myself a little more time. I thought this post was going to be my release point. But now I'm suddenly realizing that I'm still trying to hold on a moment longer.

Self-Imposed Crippling Frustration Under a Wave of Social Justice Advocacy

It was Saturday night when I knew I'd smudge myself and my house with sage the next day. There had been a build up. With the media exposure of police shootings and the new energy for social justice as a response, I was caught up in the energy. But not without personal justification. Under Trump's toxic atmosphere, my beloved Cherokee community quickly became as divisive as the rest of America.

I started to hear comments that I hadn't heard before, and this time from the mouths of racially white Cherokees. What happened? Why were dark skinned and full blood Cherokees so viscerally hated? And all of a sudden?

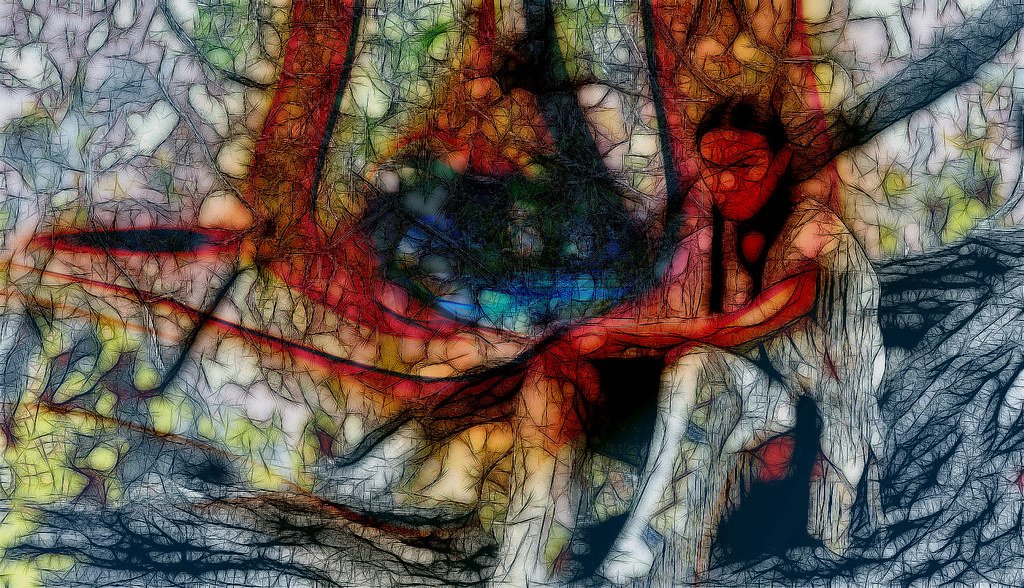

Well, it wasn't all of a sudden. This divide between full-blood, half-blood, and racially white has been a part of Native communities for a long time. We can go back as far as the initial reservation era of the 1800s. Take Quanah Parker (Comanche) for example, who is depicted in the image above. He was half white and half Comanche. While the Comanche people did not elect Quanah as their spokesperson, the U.S. government made it clear to the tribe that Quanah would be the only person they were going to deal with. So the Comanche chiefs who were elected inside the community were ignored, while Quanah was selected by those in power.

Why do Natives only gain access when we display an allegiance to white supremacy?

It's unfortunate how we can't overcome this history, where race determines power, as opposed to ability, talent, and strength. Ta-Nehisi Coates writes, “But race is the child of racism, not the father.” And we've heard since the 1990s that "race is a social construct." But then again, everything humans do is a social construct, and this particular construct has murdered millions, enslaved millions, and continues to oppress millions today.

So why was I hearing comments? Why were decisions being made that had full blood Cherokees scrambling? All of a sudden I was reminded of my teen years growing up in Tahlequah, when Cherokees were murdered for being Cherokee, when Cherokees talked about the underground culture in hushed tones, and when Cherokees all too often contorted ourselves under the boot heels of white supremacy.

Then as an adult I moved away for a decade.

When I returned to Tahlequah in 2015 I found a very different Cherokee Nation. There were liberal white Cherokees displaying themselves as allies to "identifiable" Cherokees. There was more willingness to engage and the blatant racism that I once encountered had seemed to disappear.

Then Trump was elected.

Slowly there was an erosion. I started to hear more and more underhanded comments about "identifiable" Cherokees, which is a new white supremacist term for targeting anyone who has traditional Cherokee phenotypes: Dark skin, high cheek bones, strong jawlines, narrow eyes. More and more of my racially white peers would say "Indian this" and "Indian that," and I'd think to myself, "I thought you were Indian." But according to the UNSPOKEN racial line, they were not Indian like "identifiable" Indians. Racially white Cherokees were somehow superior. This language grew and grew over the last four years until it reached a point recently where racially white Cherokees were blatantly and openly talking about "Drunk Indians" and how "identifiable" Cherokees were criminals. The tone was etched with superiority, leaving dark skinned and full blood Cherokees feeling like we had no power, like we were being targeted. And you have to understand, the majority of enrolled Cherokees are racially white. It's not a spectrum, not even close. Those of us who live and work here know the truth. "Identifiable" Cherokees are the minority. Cherokee Nation's racial makeup is identical to the U.S. The darker your skin, the harder your life.

I watched full bloods in my circles cower and back down when racist comments were made. Completely silenced. And half-bloods who have a full-blood parent biting their tongues. Some of us have spoken up, but it doesn't come without feeling like we're going to receive retaliation, retaliation for asking people to not say "drunk Indian." Can you believe that? Basic human decency. It's frustrating that we have to beg to be treated like people. It's frustrating that I have to remind folks that we're human beings. Why is it so extreme to have respect reciprocated? Why would I have to say, "I can't breathe," when it should be obvious that racism is a social choke hold?

I started writing this post wanting to write about how I needed to let go of the frustration, how maybe it was crippling me to think about it. More or less, blaming myself. But now? I wonder if racially white Cherokees ever think about crippling their own supposed brothers and sisters? That's what we're supposed to be, right? Brothers and sisters? We all come from "One Fire," right? If so, why do they make comments like their not Native? Why do they limit how many dark skinned Natives get positions of power? Why do they fear dark skin so much that they'll have just one or two "tokens" to keep in their back pockets? If we all come from "One Fire," why did I have to write this fucking post?

(Images were borrowed from commons wikipedia)

Giving Back: Murrow Indian Children's Home Needing Assistance

I get mentally stuck sometimes, and frustrated, when I think of the disparity rates in the communities I serve. I'm Cherokee and Kiowa. I live in Tahlequah, Oklahoma and work for Indian Child Welfare. I've worked my entire career serving Native communities, working diligently to correct the disparity rates, and every time I see a Native person walking down the street strung out on meth, fidgeting and impulsively picking at their skin (the telltale signs of meth addiction), it breaks my heart. I get frustrated at the disparity rates among Native Americans and see first hand the negative impacts caused by historical trauma.

There is one way to change the disparity rates and that's by giving to a well vetted Native organization, like the Murrow Indian Children's Home in Oklahoma. It's more commonly called the Murrow Home for us locals. They provide care for Native children and are currently in need of specific items. Below you'll find a link to their official Facebook page:

We all want to help and often we don't know how. While I've dedicated my career to working with Native youth, many of us have occupations outside this field but equally want to contribute. My recommendation is to go through the process of vetting Native organizations. Don't wait for a Native person to do so. It can be frustrating for people of color to always have to do the leg work. If I can care enough about Native people that I'll do the work to track down organizations and talk to employees from specific organizations, then I expect anyone could do the same. Not to be harsh, but people of color are not slaves to someone else's enlightenment. Although, when I see a Native organization sending out a call, like the one on the Facebook page above, I'll go out of my way to help them meet their needs.

If you'd like to know more about the Murrow Indian Children's Home here is a link to their website: The Murrow Home. Also, here is a link to their amazon wish list page: Amazon Smile Murrow Home. Additionally, if you'd like to learn more about the history of The Murrow Home here is an article: Cherokee Phoenix Article on The Murrow Home.

I started my career working with a Native group home so my heart is close to helping children in those troubling circumstances. I know what it's like to mentor youth who need stability and safety in their lives, who need a strong role model. The Murrow Home is a rare group home that works specifically with Native youth, including Cherokee children from tribally specific Cherokee communities. If you're in a position to give back, please do so by reaching out to The Murrow Home directly or following one the links above.

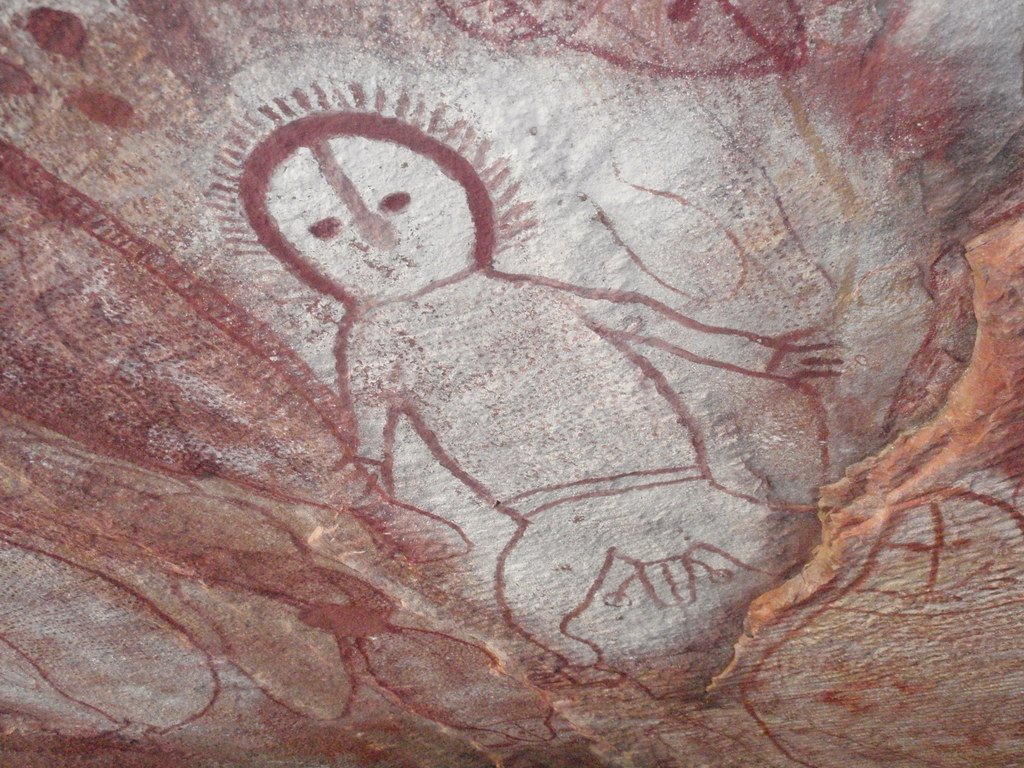

(Image above was borrowed from flickr)

Indian Child Welfare Novel: Lessons in Cooking Coded Cake

If you're getting silenced, or an attempted silence, as an artist/writer this is a sign you're doing something right. The ACLU has extensive documentation about the rights of artists to speak our minds and advocate for communities. Intimidation tactics from white supremacists didn't stop me from writing my first novel, UNSETTLED BETWEEN, and they won't stop me from writing my "ICW" novel. Power hungry racists will always fear artists. We have a power they'll never have: the ability to move audiences to connect with a deeper sense of their own humanity. You might be wondering why I'm writing this post. It's not exactly one of my typical updates on my writing projects. Usually I use this space to brainstorm concepts in a story I'm writing, but today I'd like to talk about how fiction writers can capture real life in their pages. Moreover, how artists overcome coercive tactics meant to silence our voices.

You might be wondering why I'm writing this post. It's not exactly one of my typical updates on my writing projects. Usually I use this space to brainstorm concepts in a story I'm writing, but today I'd like to talk about how fiction writers can capture real life in their pages. Moreover, how artists overcome coercive tactics meant to silence our voices. As you already know, when I write I do so from personal experience. I take what I see around me, whether in my personal life or the lives of the people in my proximity, and I transform it into a fictional space. So there are a few ways in which I pull this off. I've had people ask me, "How can you do that and not offend people?" Well, the short answer: It can still rub certain people the wrong way. But the truth and honesty in the work will always shine through and people can't deny the craftsmanship in turning real life into fiction. At the end of the day, only the villains will become detractors. Most will be flattered. I always say, "If you don't want to be a villain in fiction, the don't be one in real life."The primary things to consider are more obvious: change names, alter places, and code oppression. The issue for white supremacists is their legacy. If you, and others around you, talk and gossip about their behavior, it's already known in the community how they are oppressive. Just enough has to come to the surface before those in higher positions of power catch wind. The system will ignore oppressive acts only as long as it has to. Once something becomes news worthy, then those in the highest reaches of power will put a stop to it. The oppressors will do everything they can to keep things from getting to a boiling point. Hence the suppressive tactics and attempts at silencing artists.

As you already know, when I write I do so from personal experience. I take what I see around me, whether in my personal life or the lives of the people in my proximity, and I transform it into a fictional space. So there are a few ways in which I pull this off. I've had people ask me, "How can you do that and not offend people?" Well, the short answer: It can still rub certain people the wrong way. But the truth and honesty in the work will always shine through and people can't deny the craftsmanship in turning real life into fiction. At the end of the day, only the villains will become detractors. Most will be flattered. I always say, "If you don't want to be a villain in fiction, the don't be one in real life."The primary things to consider are more obvious: change names, alter places, and code oppression. The issue for white supremacists is their legacy. If you, and others around you, talk and gossip about their behavior, it's already known in the community how they are oppressive. Just enough has to come to the surface before those in higher positions of power catch wind. The system will ignore oppressive acts only as long as it has to. Once something becomes news worthy, then those in the highest reaches of power will put a stop to it. The oppressors will do everything they can to keep things from getting to a boiling point. Hence the suppressive tactics and attempts at silencing artists. The last thing they want is a permanent record of their hate. Remember: we're all judged by our endings. The ones in real life, and the ones we write. If the last thing people know about you is that you're a pedophile, then everyone in the community will remember you as a pedophile. It doesn't matter how much you've done before. Preying on a child, even if that child was a vulnerable disadvantaged teen, is inexcusable. And they might think people don't know they were fired from a job working with youth. But the right people always know. The next time you see them ask, "Why were you fired from that youth organization?" Likewise, if community members read coded fiction stories divulging poorly treated vulnerable populations, those in the community will know the code. They'll know who so-and-so is, and if they don't, all they have to do is ask relatives who will ask other relatives. In small town politics, word moves fast. And the power of gossip is something no one should underestimate. Believe me when I say this: Writers are seductive monsters. Our love lulls audiences into a mind altering hypnosis. And we're very aware of what we're doing. I've said this before,"We’re persuasive colonizers seeking to intrude on your sensibilities."When taking a real event, involving real life people, I not only change their names and description, but I also layer each story with other layers of truth. So what I'm doing is stacking multiple real life situations atop each other, and this turns a true story into fiction. To be completely honest, a single interesting event in real life is not good enough to entice a reader. You have to add more and more. Like sugar is the thing that makes a cake taste great, but it's the multitude of ingredients that give you the experience of eating a cake. Otherwise, we'd all be pouring bags of sugar down our throats, lol. How the ingredients are cooked together and presented make for a complete "cake experience." Turning real life into fiction works the same way.

The last thing they want is a permanent record of their hate. Remember: we're all judged by our endings. The ones in real life, and the ones we write. If the last thing people know about you is that you're a pedophile, then everyone in the community will remember you as a pedophile. It doesn't matter how much you've done before. Preying on a child, even if that child was a vulnerable disadvantaged teen, is inexcusable. And they might think people don't know they were fired from a job working with youth. But the right people always know. The next time you see them ask, "Why were you fired from that youth organization?" Likewise, if community members read coded fiction stories divulging poorly treated vulnerable populations, those in the community will know the code. They'll know who so-and-so is, and if they don't, all they have to do is ask relatives who will ask other relatives. In small town politics, word moves fast. And the power of gossip is something no one should underestimate. Believe me when I say this: Writers are seductive monsters. Our love lulls audiences into a mind altering hypnosis. And we're very aware of what we're doing. I've said this before,"We’re persuasive colonizers seeking to intrude on your sensibilities."When taking a real event, involving real life people, I not only change their names and description, but I also layer each story with other layers of truth. So what I'm doing is stacking multiple real life situations atop each other, and this turns a true story into fiction. To be completely honest, a single interesting event in real life is not good enough to entice a reader. You have to add more and more. Like sugar is the thing that makes a cake taste great, but it's the multitude of ingredients that give you the experience of eating a cake. Otherwise, we'd all be pouring bags of sugar down our throats, lol. How the ingredients are cooked together and presented make for a complete "cake experience." Turning real life into fiction works the same way. Saying so-and-so is a racist and oppresses every dark skinned person they encounter is intriguing in the most awful way possible, but when you add that so-and-so has an opiate addiction and throws women under the bus--now we're getting deep and dirty. Take that and add how their child is a meth addict and they've used their power to clear criminal charges; then all of a sudden it's getting really real. But you get the picture. It's taking multiple real life events from different people around you and smashing them together.Writers sacrifice for the solitude needed to capture an entertaining version of real life. Ultimately, no matter how "literary," that's what we're doing, that's our job: to entertain. Audiences love stories flavored with the sweetest truth, savoring each bite like the latest gossip in town. They will read and reread pages in your novel to chew on the layers, to find the truth about the people they know. Now can you imagine anything better than cake?

Saying so-and-so is a racist and oppresses every dark skinned person they encounter is intriguing in the most awful way possible, but when you add that so-and-so has an opiate addiction and throws women under the bus--now we're getting deep and dirty. Take that and add how their child is a meth addict and they've used their power to clear criminal charges; then all of a sudden it's getting really real. But you get the picture. It's taking multiple real life events from different people around you and smashing them together.Writers sacrifice for the solitude needed to capture an entertaining version of real life. Ultimately, no matter how "literary," that's what we're doing, that's our job: to entertain. Audiences love stories flavored with the sweetest truth, savoring each bite like the latest gossip in town. They will read and reread pages in your novel to chew on the layers, to find the truth about the people they know. Now can you imagine anything better than cake?

(Images were borrowed from pixabay, pxfuel, piqsels and flickr)

Mexican Indian: The Shifting Indigenous Identity of Turtle Island

Call it evolution or enlightenment. Our perspective is broadening. Where we once only had the capacity to see ourselves in strict hyper local terms, now we can access the universal. In fact, both the universal and the hyper local are needed as checks and balances. In the narrow reaches of our identity, people are quick to lock themselves into violent identities--those in need of contention to exist, to be relevant, to matter. It takes a little dialectical thinking to incorporate a universal identity, where we have the intellectual capacity to, simultaneously, know how we are all connected.

Let me give you a little context and my personal ethos.

My father was an immigrant from Chihuahua, Mexico. My mother is a full blood Kiowa/Cherokee from Oklahoma, United States. I am a product of intertribal, multicultural, transnational, and hyper local tribal histories. Oklahoma was once known as Indian Territory and became the world's largest Prisoner of War camp. Chihuahua was once home to 200 tribes before Spanish conquistadors committed genocide to mine silver from the region's mountains.

When I look south of the American border, I remember being five years old and running into the Chihuahua mountains with my cousins to shoot homemade slingshots. I also remember the Indigenous phenotypes of Indigenous ancestors in my cousin's faces. Having been raised in Oklahoma primarily with my Kiowa and Cherokee people, my perspective has always been an Indigenous one--even before I knew the meaning of the word. I rightly assumed all my cousins in Mexico were Indigenous like myself, since we had the same brown skin, narrow eyes, and black hair. The truth expounded by innocence is always convoluted by fragile adults seeking power over people.

The Náhuatl Language in México: http://www.houstonculture.org/mexico/nahuatl.html

I grew up attending traditional powwows with Kiowa and Comanche people in southern Oklahoma, dancing with my family, wearing bright regalia made by my mother's and aunt's hands. In my youth, we "lived" at the powwow grounds for days at a time. Camping in a tent was as common as sleeping in my bed. While I was one of a few Kiowas with Mexican heritage, we all had the same phenotypes. I didn't look any different from my family, and certainly wasn't treated differently.

Because in my youth I had experiences in Chihuahua, Mexico and experiences in Oklahoma, United States, as an adult the border between Mexico and the U.S. seems arbitrary. Drawn by power seekers and maintained, physically and psychologically, to keep Indigenous people from acknowledging our commonality. Which begs the question, why are colonizers so afraid of Indigenous people allying with each other across Turtle Island?

I'm reminded of the various tribal confederacies in North America who once attempted to unify Indigenous people, and the most famous in the U.S. was Tecumseh's Confederacy (Chief Tecumseh Urges Native Americans to Unite), which ultimately lead to siding with European allies in the struggle for retaining control of traditional lands. Similarly, there were alliances on the Southern Plains of North America, where Kiowas allied with Comanches and held back westward expansion for 100 years (Oklahoma Historical Society). Once they extended their alliance to include the Cheyenne and Arapaho tribes, a confederacy of Indigenous tribes dominated the Southern Plains of North America.

Needless to say, the circumstances that drove Indigenous people in the past are radically different than our need to unify today. Where land base was a primary mode of those alliances, today we are tasked with protecting not only a way of life but more importantly how that way of life is inextricably tied to land based practices. Moreover, to stand against the contamination of earth, air, and water--the three elements needed for human survival. Our plight to unify isn't strictly for the benefit of Indigenous peoples, but for all people to survive and live healthy lives. The environmental war being waged against Indigenous people in Canada is the same war being waged against Indigenous people in Mexico. Whether we're looking north or south, we, as Indigenous people in the United States, have allies in both directions. Why would we limit ourselves to myopic, hyper local identities? Because of a language barrier? Our ancestors developed sign languages to navigate dozens of tribal languages. So we can't beat one colonial language? We're as smart as our ancestors and have the intelligence to know how outdated people lock themselves into identities based in violence. We're smart enough to unfollow and unfriend and silence those seeking to keep Indigenous people from unifying. Outdated practices will only serve to keep Indigenous people fighting with each other, where neo-tribal politics can see the unifying history--how Native people were not only forced to flee into Canada, but to also flee into Mexico.

And now it's time for a return.

(Images were borrowed from The Canadian Encyclopedia, Pinterest, and Facebook.)

The 12 Year Journey of Unsettled Between

I spend a lot of time thinking about love, and what I'm about to discuss here is in the vein of love. But a love for cohesiveness, a love that desires modalities in cooperation rather than competition. Certainly, it took the very pessimistic concepts around Baudrillard's philosophy to engender my thoughts on this subject. But without Baudrillard I would've never reached this conclusive ending: competition is a mere copy of a copy. I hear you asking "So then what's the original source?" My answer: inspiration. I've spent the last 14 months adding to and then revising a novel. It jumped from approximately 30,000 words to 73,000 words inside of a few short months. Then came all the revisions. I dove into each story and read and reread sentence after sentence, smoothing out the edges and slicing deeper details. Unsettled Between has changed dramatically and in the most beautiful ways. The thematic concept is much cleaner. The stories are further developed. The characters have richer personalities--all the characters--whether static or dynamic. And how was I able to alter a few stories into a full length novel? Inspiration.I'm going to be real honest here. Before I found representation for my novel, I had lost a great deal of inspiration. As many writers can in the ups and downs of life. I had written a couple of the stories in Unsettled Between from 2008 to 2010. They were published in journals ("Our Day" in American Short Fiction and "Time Like Masks" in South Dakota Review"). It was enough to give me a surge of inspiration. Success, even modest success, can give a writer enough fuel to burn for a full length novel.I sent one of the stories to Oxford American, which is a journal I dream of getting published with, and the editor turned it down but he wrote a little note in the corner saying something to effect of "Please submit more fiction in the future. I enjoyed your story," and this little note gave me additional inspiration to continue. So I completed a few more stories, and then a few more, and soon I had enough stories to call this a novel. But it was weak. It needed a lot of development.

I've spent the last 14 months adding to and then revising a novel. It jumped from approximately 30,000 words to 73,000 words inside of a few short months. Then came all the revisions. I dove into each story and read and reread sentence after sentence, smoothing out the edges and slicing deeper details. Unsettled Between has changed dramatically and in the most beautiful ways. The thematic concept is much cleaner. The stories are further developed. The characters have richer personalities--all the characters--whether static or dynamic. And how was I able to alter a few stories into a full length novel? Inspiration.I'm going to be real honest here. Before I found representation for my novel, I had lost a great deal of inspiration. As many writers can in the ups and downs of life. I had written a couple of the stories in Unsettled Between from 2008 to 2010. They were published in journals ("Our Day" in American Short Fiction and "Time Like Masks" in South Dakota Review"). It was enough to give me a surge of inspiration. Success, even modest success, can give a writer enough fuel to burn for a full length novel.I sent one of the stories to Oxford American, which is a journal I dream of getting published with, and the editor turned it down but he wrote a little note in the corner saying something to effect of "Please submit more fiction in the future. I enjoyed your story," and this little note gave me additional inspiration to continue. So I completed a few more stories, and then a few more, and soon I had enough stories to call this a novel. But it was weak. It needed a lot of development.  It was 2012 and I wanted some type of success. I needed inspiration. I knew if I could get someone to grab onto my book I'd have renewed energy. So I started sending out queries and got a request for a partial but the agent never even gave me a "No, thank you." The request came quickly in my querying process so I stopped sending out queries, which turned out to be a mistake. The agent never returned my email. And I emailed a few times asking for updates. But nothing. I was young in my career and took this as a defeat. In hindsight, I should've just kept querying. I hadn't submitted to very many agents. But I was naive and new to the game. I was defeated, or felt defeated, like maybe giving up was the only option. Soon I stopped carrying around my laptop and I forgot about the flash drives.A few years passed. I got divorced. Moved back to Oklahoma. Started raising my kids as a single parent. Life swept in like a tornado and carried me into a version of myself I didn't recognize.

It was 2012 and I wanted some type of success. I needed inspiration. I knew if I could get someone to grab onto my book I'd have renewed energy. So I started sending out queries and got a request for a partial but the agent never even gave me a "No, thank you." The request came quickly in my querying process so I stopped sending out queries, which turned out to be a mistake. The agent never returned my email. And I emailed a few times asking for updates. But nothing. I was young in my career and took this as a defeat. In hindsight, I should've just kept querying. I hadn't submitted to very many agents. But I was naive and new to the game. I was defeated, or felt defeated, like maybe giving up was the only option. Soon I stopped carrying around my laptop and I forgot about the flash drives.A few years passed. I got divorced. Moved back to Oklahoma. Started raising my kids as a single parent. Life swept in like a tornado and carried me into a version of myself I didn't recognize.

“When I sit down to write a book, I do not say to myself, ‘I am going to produce a work of art.’ I write it because there is some lie that I want to expose, some fact to which I want to draw attention, and my initial concern is to get a hearing.” — George Orwell

Then in 2015, I got this idea for a novel. Not the collection of stories I had written. Those stories I couldn't even look at. In fact, I couldn't even slide the flash drive with those stories into a USB. There was something psychological keeping me from going back. I told myself I needed to move forward. Keep thinking positive. So I wrote another novel, Uncle Called Him Spider. You can find posts on this blog where I work out kinks in the storyline. But this new idea was enough to get me believing I was a writer again. 60,000 words later. I had no doubt.So being in awe of my accomplishment. Writing 60,000 words is heavy lifting and it took me about six months to complete the first draft. Then I started the revisions and deepening the novel. After a year I had a solid "draft" of Uncle Called Him Spider. It was solid enough to call a draft and had interlaced subplots with protagonist and antagonist battling for top spot in a very esoteric field. It was different. I hadn't read a novel like it before so it left me feeling good about my hard work.

“There are no laws for the novel. There never have been, nor can there ever be.” — Doris Lessing

So late 2017 and early 2018, I start thinking about those stories. I'm like, "Maybe I should try to reread a few of them." Then a friend asked if I was working on any fiction. I told him about the new novel, but in the back of my mind I thought about those stories. His very considerate and thoughtful question was a springboard. Suddenly, I started thinking about the collection of stories again.I decided to try to slide a "certain" flash drive into a USB. And it worked. After reading the collection, I suddenly had a new vision for the book. So most of the stories were booted. They either didn't fit into this new concept or I felt like they just weren't good enough. So I wrote new stories. Then I polished them to a point where they were more than solid. They were ready to be published in journals. But my earlier defeat left me too frail to consider putting myself on the line. I couldn't handle the rejection, or the repeated rejection. Maybe one or two. But the dozens it can take to get a story published was going to be too much.

“If it sounds like writing, I rewrite it.” — Elmore Leonard

Then I heard of this event on Twitter. It was called #Dvpit (Diverse Voice Pitch) event. It was a simple but brilliant concept. You developed a twitter sized pitch of your novel. On the day of the event, you post the tweet. If an agent clicks on the heart icon, then you send them their requested material. I thought, this isn't nearly as brutal as the traditional querying process. I told myself, "It's a one time pitch," as opposed to the numerous I was visualizing. More importantly, it avoided the numerous rejections. Plus, it was new, different, and I got a little excited about it. So I marked it on my calendar and wrote a pitch. I polished over several weeks, reading and rereading until it was tight and succinct.I was surprised when multiple agents from large literary agencies started clicking on my tweet. What I liked most was how this pitching event gave me a sense that I was on the right track. It gave me inspiration. Long story short, I landed an agent. I couldn't believe my luck. The excitement carried over into the revision process. I was so beyond inspired that when my agent asked me to more than double the novel, I did so in a few short months. It almost felt easy. Likely because I was inspired by the success of working with an agent and speaking with someone who cared as much about my novel as I did. I can't tell you how lucky I am to be working with my agent, Allie Levick. I highly recommend querying her if you have a full manuscript to offer. As I reflect back on the last 14 months, she has asked me to look at specific pieces of the story in new ways. She's very hands on with the development and cares a lot about her work. I have high standards when it comes to professionalism. Allie carries herself as a true professional and I highly respect her opinion. A good agent will offer creative feedback, but one steeped in the rigors of her profession will inspire.So over the last few weeks, as I disappeared into revision work, I've thought a lot about things, like Baudrillard and love, cohesion and cooperation. I've seen people using "competition" to work themselves up. But I find inspiration to be the most impacting on art and life. In fact, from the competitiveness I've witnessed, I can see how inspired people energize themselves and the uninspired feed off the inspiration of others. Competition is only a fading copy of inspiration. Personally, I simply seek out inspiration or wait for it and trust it'll find its way toward me. Then once my spirit has risen with its power, I hold onto it as long as I can.

I can't tell you how lucky I am to be working with my agent, Allie Levick. I highly recommend querying her if you have a full manuscript to offer. As I reflect back on the last 14 months, she has asked me to look at specific pieces of the story in new ways. She's very hands on with the development and cares a lot about her work. I have high standards when it comes to professionalism. Allie carries herself as a true professional and I highly respect her opinion. A good agent will offer creative feedback, but one steeped in the rigors of her profession will inspire.So over the last few weeks, as I disappeared into revision work, I've thought a lot about things, like Baudrillard and love, cohesion and cooperation. I've seen people using "competition" to work themselves up. But I find inspiration to be the most impacting on art and life. In fact, from the competitiveness I've witnessed, I can see how inspired people energize themselves and the uninspired feed off the inspiration of others. Competition is only a fading copy of inspiration. Personally, I simply seek out inspiration or wait for it and trust it'll find its way toward me. Then once my spirit has risen with its power, I hold onto it as long as I can.

Support a Native owned Etsy shop, Allies United, where I offer unique merch for allies of social justice movements, like MMIW, Native Lives Matter and Black Lives Matter. Take a look inside my Etsy shop here: etsy.com/shop/AlliesUnited.

(Images were borrowed from wikipedia, columbus,af.mil, and pxfuel)

How to Smudge with Sage & Native American Customs for Prayer

I've had several people inquire about practices and customs associated with smudging. I decided to cleanse myself today so I thought I'd make a short video on rituals I've learned over the years. This is by no means anything dogmatic. These are just methods that I've learned over the years. I'm Kiowa and Cherokee, and I've incorporated practices between both cultures and lessons I've learned personally through doing this routinely that work for me.I hope you enjoy the video. Please feel free to share with as many folks as you like, and if you have questions reach out to me in the comments. Wa'do, have a blessed day, and if you're interested in Native American fiction please support my debut novel, CALLING FOR A BLANKET DANCE: Bookshop, Amazon, B&N, IndieBound.https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Z3GGFIfJY0Q

#WritersLife: When Writers Dream of Characters in Their Novel

#WritersLife was the first thought I had when I woke. But I couldn't shake the deep depression taking control of me. I felt an immense sadness. It felt like I was so inadequate that I didn't matter to anyone. My life was so pointless and meaningless that no one would ever want to connect with me enough to care about my life. My mind kept circling around about how shitty a human being I was and how it didn't matter what I thought or felt. My chest was heavy, shoulders sunken, and I could feel the length of my jaw pulling downward. I had little energy. Just enough to zombie through the last two days. And it started with a vivid dream about a character, Jimena, in my novel, Unsettled Between.I've never had a reaction like this before. I've dreamt about characters and scenes and concepts for novels or short stories before (often in the waking moment between sleep and full consciousness), but I've never had such an emotional reaction. It's really odd and I'm still feeling remnants of it now. Yesterday was the worst of it.I'm not an emotional person. I get sad, but I don't tend to linger in it to a point I would call depression. I've been depressed before, but I tend to force myself into tasks that help alleviate those feelings. So when this feeling grabbed me over the last two days it was very alien, like someone else had stepped inside my body and had taken over.

And it started with a vivid dream about a character, Jimena, in my novel, Unsettled Between.I've never had a reaction like this before. I've dreamt about characters and scenes and concepts for novels or short stories before (often in the waking moment between sleep and full consciousness), but I've never had such an emotional reaction. It's really odd and I'm still feeling remnants of it now. Yesterday was the worst of it.I'm not an emotional person. I get sad, but I don't tend to linger in it to a point I would call depression. I've been depressed before, but I tend to force myself into tasks that help alleviate those feelings. So when this feeling grabbed me over the last two days it was very alien, like someone else had stepped inside my body and had taken over. The dream was about me interacting with a character, Jimena. She's not a major character in my novel but she's important to certain stories in the collection.In the dream, Jimena lead me from one place to another but it was almost like I was floating around her as opposed to her leading me. It was like I took on her energy so she could act "normal" or front like she was okay. I watched as she displayed happiness and confidence to people around her, but I carried her sadness. That's weird, isn't it? How could I carry sadness for her?Another odd occurrence happened when I woke. There was a lightening flash that lit up my bedroom. It was so bright I thought it was storming outside. We had rain the day before so I thought maybe storms had come in overnight. But when I looked outside it was overcast but no storms. The flash was like a strobe coming from inside my room--not outside.Now I've carried this unbearable sadness with me for two days. The depression is so harsh that I haven't gotten on social media in the last two days. I'm a junkie or have bouts of social media binges so going two days with no interest in social media is odd. This is likely the case for many of us.

The dream was about me interacting with a character, Jimena. She's not a major character in my novel but she's important to certain stories in the collection.In the dream, Jimena lead me from one place to another but it was almost like I was floating around her as opposed to her leading me. It was like I took on her energy so she could act "normal" or front like she was okay. I watched as she displayed happiness and confidence to people around her, but I carried her sadness. That's weird, isn't it? How could I carry sadness for her?Another odd occurrence happened when I woke. There was a lightening flash that lit up my bedroom. It was so bright I thought it was storming outside. We had rain the day before so I thought maybe storms had come in overnight. But when I looked outside it was overcast but no storms. The flash was like a strobe coming from inside my room--not outside.Now I've carried this unbearable sadness with me for two days. The depression is so harsh that I haven't gotten on social media in the last two days. I'm a junkie or have bouts of social media binges so going two days with no interest in social media is odd. This is likely the case for many of us. Initially, I tried to work this out as some residual part of my past, like something Jungian I hadn't addressed. But then suddenly I realized the character goes through something in the novel that was emotionally challenging for her. But I didn't give it the emotional weight. Meaning, maybe I wasn't honest enough about how much she hurt. I wish I could tell you what specifically I'm talking about in the novel, but I'm going to have to wait until it's released before I can put the two together.Ultimately, I feel like I didn't do her character justice and she came to me in my dream to show me how she felt. That sounds odd, I know. But I can't make sense of why I'd have these emotions associated to that dream about this specific character. It's the only conclusion I can draw.In fact, I had to write my agent, who received my most recent draft a couple weeks ago. I told her about the dream, and she gave me the green light to go back into the novel and revise Jimena's portion. I do feel better now that I can revise to Jimena's liking. But what an interesting emotional ride. As a writer, I sometimes feel like I know how to pull details from my psyche to write about. But this is a first.Have you dreamed about a character in one of your story lines? If so, what was your experience? A part of me is desperately searching for kindred spirits. I hope I'm not alone in this. I'm hoping this is one of those #WritersLife hashtag moments.

Initially, I tried to work this out as some residual part of my past, like something Jungian I hadn't addressed. But then suddenly I realized the character goes through something in the novel that was emotionally challenging for her. But I didn't give it the emotional weight. Meaning, maybe I wasn't honest enough about how much she hurt. I wish I could tell you what specifically I'm talking about in the novel, but I'm going to have to wait until it's released before I can put the two together.Ultimately, I feel like I didn't do her character justice and she came to me in my dream to show me how she felt. That sounds odd, I know. But I can't make sense of why I'd have these emotions associated to that dream about this specific character. It's the only conclusion I can draw.In fact, I had to write my agent, who received my most recent draft a couple weeks ago. I told her about the dream, and she gave me the green light to go back into the novel and revise Jimena's portion. I do feel better now that I can revise to Jimena's liking. But what an interesting emotional ride. As a writer, I sometimes feel like I know how to pull details from my psyche to write about. But this is a first.Have you dreamed about a character in one of your story lines? If so, what was your experience? A part of me is desperately searching for kindred spirits. I hope I'm not alone in this. I'm hoping this is one of those #WritersLife hashtag moments.

Support a Native owned Etsy shop, Allies United, where I offer unique merch for allies of social justice movements, like MMIW, Native Lives Matter and Black Lives Matter. Take a look inside my Etsy shop here: etsy.com/shop/AlliesUnited.

(Images were borrowed from wikimedia, wikipedia, and flikr)

On Writing an "Indian Child Welfare" Novel & Other Grand Adventures

I hiked into the Grand Canyon. I must've been in my late twenties, maybe early thirties. It started out as a walk to look over the rim. I had camped the night before in a tent at one of the sites and woke early (probably about 5am). I was there with a friend and she was still asleep. As the sun rose out of the east, I decided to follow the paved roads toward the rim of the Grand Canyon. It was nice to be out so early in the morning. No one was around. It felt like the entire world was mine alone. I strolled on the sidewalk lining the edge of the Grand Canyon mesmerized by the depth of the canyon and the streaming sunlight slowing filling it's center. It was beautiful, magical, and most of all peaceful.Then I happened upon an entrance. I didn't expect to find an invitation that day.

It was nice to be out so early in the morning. No one was around. It felt like the entire world was mine alone. I strolled on the sidewalk lining the edge of the Grand Canyon mesmerized by the depth of the canyon and the streaming sunlight slowing filling it's center. It was beautiful, magical, and most of all peaceful.Then I happened upon an entrance. I didn't expect to find an invitation that day.

“You can always edit a bad page. You can't edit a blank page.” ―

Similarly, I find stories as I stroll through my everyday. I'm always vigilant and, after being trained by the Institute of American Indian Arts and the University of Oklahoma, I see every moment as a beginning, middle, and end (a story).I've said this before. I write what I live, and create fiction by moving experiences around, compounding memories, and enhancing the "feeling" of a moment with embellishments. But embellishments can be made into entertainment when delivered as a book-sized package.I have three writing projects at the moment. Those of you who follow my blog likely know about two of those projects. The development of my novel, Uncle Called Him Spider, has been highlighted on this blog, and you can go back and find the collapse and expansion of those words in posts such as Gossip: Weapon of the Weak. It's in full first draft mode. I've revised a little but I've put it on hold. In fact, the reason I put it on hold lead me to another novel, or a novel-in-stories: Unsettled Between.

“A short story I have written long ago would barge into my house in the middle of the night, shake me awake and shout, 'Hey, this is no time for sleeping! You can't forget me, there's still more to write!' Impelled by that voice, I would find myself writing a novel.” ―

Unsettled Between began a decade ago. It's ten years in the making. I wrote one of it's first stories, Our Dance, with the help of instructors and classes at the Institute of American Indian Arts--this was around 2008. It was then published in 2010 with American Short Fiction. Then I developed another of it's stories, Time Like Masks, while completing my Master's Degree at the University of Oklahoma. It was picked up by South Dakota Review in 2011. Now, those stories are two of twelve in my novel, Unsettled Between. I'm proud to say it's rep'd by Allie Levick of Writers House.This brings me to the third project. This one is very recent. I'm calling it my "Indian Child Welfare" novel, as I develop the story-line to completion. As I had with Uncle Called Him Spider, I'll be brainstorming different components of the novel here on my blog. So be sure to click the "follow" button (not to sound too much like a YouTube video). I'm not going to give away much detail on this story. I tend to hold off on full disclosure until the novel has reached fruition. But as you read posts you'll be able to piece together what I'm struggling with, as far as what I need to capture, and where the novel is headed.

“You write about experiences partly to understand what they mean, partly not to lose them to time. To oblivion. But there's always the danger of the opposite happening. Losing the memory of the experience itself to the memory of writing about it.” ―

But I will say this: I've outlined 25 chapters and have developed a full synopsis of the novel at this point. I've worked out details that drive the action. But I've not written the first draft. That's my next step. So be sure to come back and check in. You'll find my frustrations and triumphs listed here. Often my brainstorming sessions show up at odd and unpredictable times. I'll also add: The world of child welfare is not what you think. I've worked for over ten years with at-risk populations and you might believe heroism has a certain purist quality to it, but I'll dispel that for you. I have a cast of characters in this "Indian Child Welfare" novel that'll both affirm and disrupt your belief in how people carry themselves in this field. When I say you'll be shocked, it's not about the obvious things. I don't dabble in the obvious. I advocate to "bare witness" to the unseen. No more secrets. So back to my trek into the Grand Canyon. I hiked halfway down that day. I passed people hiking back up (exhaustion on their faces) and people riding donkeys (scary). It was beautiful watching the morning light grow into full afternoon. At the halfway point, there was a watering station. I filled my water bottle, sat next to other hikers in the shade, and contemplated on how easy it was to climb down.I realized that around four hours had passed and I needed to get back to camp. I hadn't told my companion that I was leaving. She was still asleep. I didn't want to wake her. Besides, I thought I was going on a light walk to the rim and back. Surely, I'd have returned before she woke. Then I ended up halfway down into the Grand Canyon. Needless to say, I drank as much water as my stomach could hold, refilled my water bottle, and started the trek back up.Three steps into climb and I thought, "Oh shit, what did I get myself into?" My legs suddenly grew tight and each step became work. I had used a different set of muscles to cruise down the edges of the canyon. Now I had to use larger muscles to climb up. Long story short, six hours later I finally pulled myself out of the canyon and back to the rim. If not for a kind and generous young man, who walked a good portion of the hike alongside me, maybe it would've take me longer. He was ten years younger and already a good conversationalist. Somehow I made it back to the rim and, by the time I made it back to camp, the sun was starting to set in the west.

So back to my trek into the Grand Canyon. I hiked halfway down that day. I passed people hiking back up (exhaustion on their faces) and people riding donkeys (scary). It was beautiful watching the morning light grow into full afternoon. At the halfway point, there was a watering station. I filled my water bottle, sat next to other hikers in the shade, and contemplated on how easy it was to climb down.I realized that around four hours had passed and I needed to get back to camp. I hadn't told my companion that I was leaving. She was still asleep. I didn't want to wake her. Besides, I thought I was going on a light walk to the rim and back. Surely, I'd have returned before she woke. Then I ended up halfway down into the Grand Canyon. Needless to say, I drank as much water as my stomach could hold, refilled my water bottle, and started the trek back up.Three steps into climb and I thought, "Oh shit, what did I get myself into?" My legs suddenly grew tight and each step became work. I had used a different set of muscles to cruise down the edges of the canyon. Now I had to use larger muscles to climb up. Long story short, six hours later I finally pulled myself out of the canyon and back to the rim. If not for a kind and generous young man, who walked a good portion of the hike alongside me, maybe it would've take me longer. He was ten years younger and already a good conversationalist. Somehow I made it back to the rim and, by the time I made it back to camp, the sun was starting to set in the west. I apologized profusely to my companion, but she was kind about it all and made her own adventures that day. She, an artist herself, knew the flights of fancy we creative types tend to have. To this day, I can find myself on peculiar adventures at a moment's notice. And like novel writing, we stumble upon an entrance and dare ourselves to take the invitation. When we think we've completed the journey, we look up and find our challenge is only halfway complete. So here's to the next few steps.

I apologized profusely to my companion, but she was kind about it all and made her own adventures that day. She, an artist herself, knew the flights of fancy we creative types tend to have. To this day, I can find myself on peculiar adventures at a moment's notice. And like novel writing, we stumble upon an entrance and dare ourselves to take the invitation. When we think we've completed the journey, we look up and find our challenge is only halfway complete. So here's to the next few steps.

(Images were borrowed from flickr, pxhere, and wikipedia)

Underground Matriarchy: #WIP Debut Novel "Unsettled Between"

We've heard the reified stories of men brutalizing men. A rehearsal of patriarchy. In fact, hyper masculine bullshit permeates our lives. We see in the media, if not in our daily lives, the ramifications of patriarchy unchecked. So what's the answer? Men are being called out now more than ever and violence continues. Wars haven't stopped. We hear about a mass shooting in the U.S. almost everyday. In my debut novel, Unsettled Between, Ever Geimausaddle faces his own brutality with the help of an underground matriarchy.

There are subcultures who maintain the values of matriarchy throughout the U.S. I'll speak here about tribal matriarchy because my experiences are based in Cherokee and Kiowa communities and culture. I'm also fortunate to belong to a family of matriarchs, where women in our family make the major decisions and delegate responsibilities.

"Our mothers echoed words they had echoed before—this time we listened. 'Being Kiowa will forever be about how we dance together.' Seemed like, being sisters, those words were a song that made them family, but more important: it made all Kiowas come together." -- Unsettled Between

Ever Geimausaddle finds himself being witness to brutality and subjected to abuse, where he develops deeply aggressive behavior. We also see this occur often in poor and disparagged communities. Ever's circumstances are no different. He encounters numerous examples of violence and domineering masculine attitudes, whether it's violence handed down from his father or colonial violence handed down from a history of conflict.

How does Ever handle these challenges? Better yet, how do the matriarchs in his family direct him? Moreover, are there matriarchal males present in his family to be role models?

"I ran into the living room, calling for my mother—ready to tattle, tell, and cry—but there was an old man sitting on the couch. He held this heavy coffee colored cane at his side. His skin had the texture of a turtle’s hide. His jaw seemed to hang lower than normal. My mother was at the store, he told me, introduced himself as an uncle, he claimed, a Bird Clan member, someone distant but a relative." -- Unsettled Between

At the end of the day, issues revolving around this current version of patriarchy needs to also be addressed by men. We, men, need to understand and then purge the violence we're trained to rehearse. Those of us who are more progressive, or who are willing to change, understand the ultimate self-destructiveness hyper masculine constructs bring.

"We were known as messengers. Cherokees depended on the Bird Clan to care for children who delivered original instructions between the spirit and material worlds. Bird Clan mothers protected birds in practical and ceremonial ways." -- Unsettled Between

Ever Geimausaddle was born into violence, rehearses violence, but he doesn't have to perpetuate violence to the next generation. In fact, if he can learn the lessons from the matriarchs in his family, he could potentially become the answer his tribal communities need: a male standing against patriarchy.

Support a Native owned Etsy shop, Allies United, where I offer unique merch for allies of social justice movements, like MMIW, Native Lives Matter and Black Lives Matter. Take a look inside my Etsy shop here: etsy.com/shop/AlliesUnited.

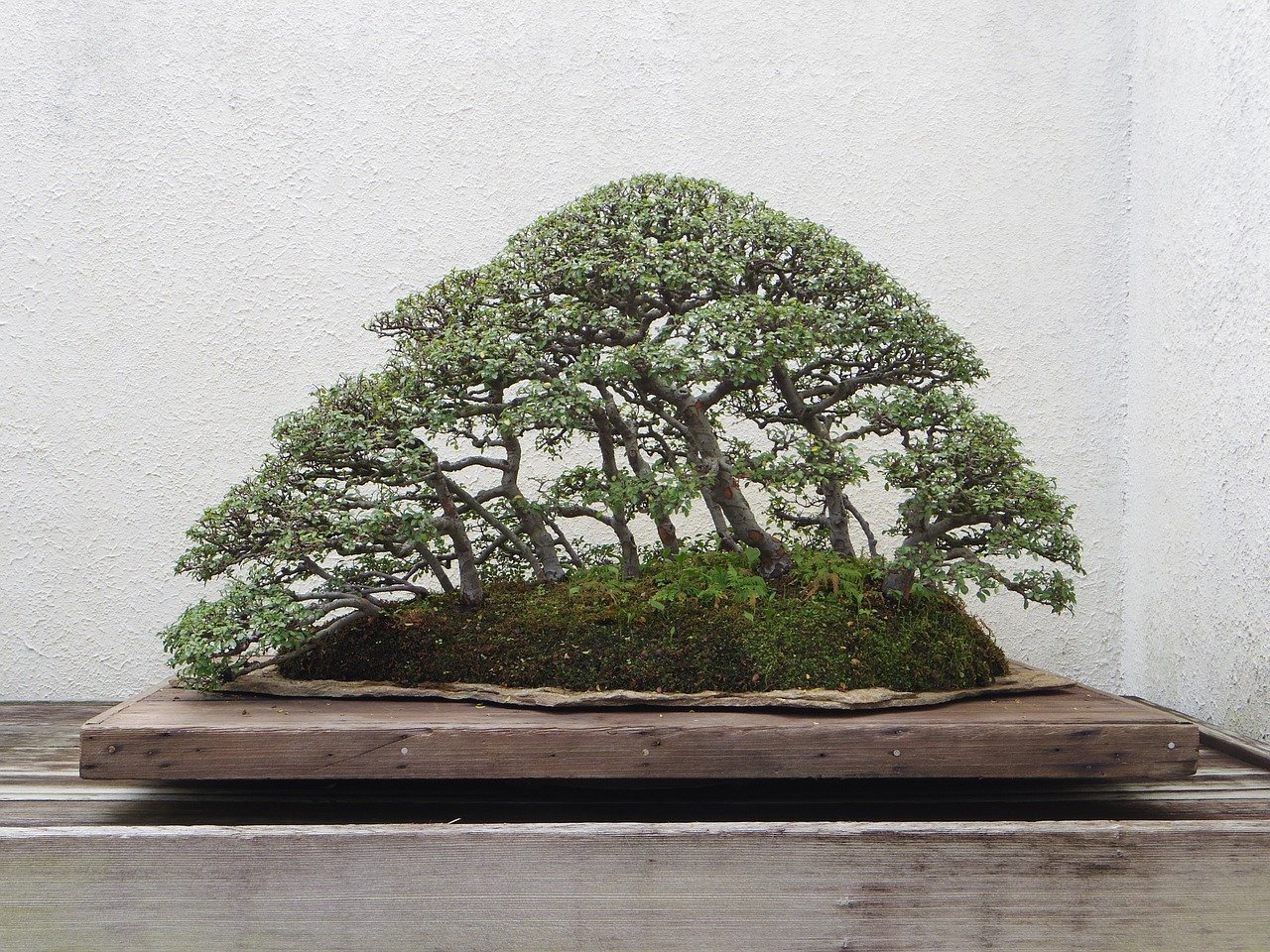

Story Like Bonsai are Reborn through Deadlines & Transformations

Like clipping and pruning back branches on a bonsai tree. Then we wire and train those branches to spread in the appearance of organic design reflective of the natural environment, taking careful consideration and steady hands. We have to make the right decisions. I've been revising Unsettled Between over the last two months and it's been a transformative process not only for the novel but for me as well. Writers get the pleasure of constant reflection, taking what's occurred in our own life and looking for material. I've always used my personal experiences to write fiction. There is no better way to draw unique and resonate stories. When I have a personal investment in the story, I tend to write with more intensity. This transfers well to the reader. They get more emotion and have a stronger connection to the characters. When I can relate to a character, whether this is in likeable or unlikable ways, I tend to be more interested to know how the story will turn out.I'm reminded of Alice Munro's short story, Child's Play. The main character is terribly unlikable. She's bitterly judgmental and cold. Then ultimately she commits the worst act imaginable. I've read this story at least two dozen times, and I shake my head every time I come to the ending. Munro expertly develops a character who I simultaneously hate and for some reason: I can't turn away. I have to read to the last word. And it pays off.Then I wonder if this character's personality is reflective of someone in Munro's life. Where did she get the inspiration to draw such a character?I turned in revisions for my novel, Unsettled Between, today. Today was the deadline. And I love deadlines. And I love feedback. Like cultivating bonsai, feedback and deadlines give me the shape and inspiration to complete a naturally flowing design for a novel.

Writers get the pleasure of constant reflection, taking what's occurred in our own life and looking for material. I've always used my personal experiences to write fiction. There is no better way to draw unique and resonate stories. When I have a personal investment in the story, I tend to write with more intensity. This transfers well to the reader. They get more emotion and have a stronger connection to the characters. When I can relate to a character, whether this is in likeable or unlikable ways, I tend to be more interested to know how the story will turn out.I'm reminded of Alice Munro's short story, Child's Play. The main character is terribly unlikable. She's bitterly judgmental and cold. Then ultimately she commits the worst act imaginable. I've read this story at least two dozen times, and I shake my head every time I come to the ending. Munro expertly develops a character who I simultaneously hate and for some reason: I can't turn away. I have to read to the last word. And it pays off.Then I wonder if this character's personality is reflective of someone in Munro's life. Where did she get the inspiration to draw such a character?I turned in revisions for my novel, Unsettled Between, today. Today was the deadline. And I love deadlines. And I love feedback. Like cultivating bonsai, feedback and deadlines give me the shape and inspiration to complete a naturally flowing design for a novel. And like anything worth doing, I learned something new about myself during this round of revisions. Or maybe it was a remembering. That I can't force anything. The first month, July, I had such a hard time. I needed to replot my opening chapter so in essence it was going to become a different story, like making a tree into a bonsai--transformation was needed. It all came out and I was very pleased with the outcome, but the story seemed to want to do things on it's own timeline. The story told me what it wanted. I didn't tell it. This was something I knew--to allow the story to shape itself--but there was a part of me that wanted to force things to happen. And I was beat back everytime I tried.Once I let go, the story wrote itself. It was organic. The branches grew toward the sun and it became a much more pleasing process. Certainly, I pruned and trimmed and clipped a few leaves here and there. What bonsai enthusiast wouldn't? What writer wouldn't? But I worked with the structure rather than forcing it. The two main characters, protagonist and antagonist, battled it out and wrote the story for me. I simply sat back and watched the story manifest.