Mexican Indian: The Shifting Indigenous Identity of Turtle Island

Call it evolution or enlightenment. Our perspective is broadening. Where we once only had the capacity to see ourselves in strict hyper local terms, now we can access the universal. In fact, both the universal and the hyper local are needed as checks and balances. In the narrow reaches of our identity, people are quick to lock themselves into violent identities--those in need of contention to exist, to be relevant, to matter. It takes a little dialectical thinking to incorporate a universal identity, where we have the intellectual capacity to, simultaneously, know how we are all connected.

Let me give you a little context and my personal ethos.

My father was an immigrant from Chihuahua, Mexico. My mother is a full blood Kiowa/Cherokee from Oklahoma, United States. I am a product of intertribal, multicultural, transnational, and hyper local tribal histories. Oklahoma was once known as Indian Territory and became the world's largest Prisoner of War camp. Chihuahua was once home to 200 tribes before Spanish conquistadors committed genocide to mine silver from the region's mountains.

When I look south of the American border, I remember being five years old and running into the Chihuahua mountains with my cousins to shoot homemade slingshots. I also remember the Indigenous phenotypes of Indigenous ancestors in my cousin's faces. Having been raised in Oklahoma primarily with my Kiowa and Cherokee people, my perspective has always been an Indigenous one--even before I knew the meaning of the word. I rightly assumed all my cousins in Mexico were Indigenous like myself, since we had the same brown skin, narrow eyes, and black hair. The truth expounded by innocence is always convoluted by fragile adults seeking power over people.

The Náhuatl Language in México: http://www.houstonculture.org/mexico/nahuatl.html

I grew up attending traditional powwows with Kiowa and Comanche people in southern Oklahoma, dancing with my family, wearing bright regalia made by my mother's and aunt's hands. In my youth, we "lived" at the powwow grounds for days at a time. Camping in a tent was as common as sleeping in my bed. While I was one of a few Kiowas with Mexican heritage, we all had the same phenotypes. I didn't look any different from my family, and certainly wasn't treated differently.

Because in my youth I had experiences in Chihuahua, Mexico and experiences in Oklahoma, United States, as an adult the border between Mexico and the U.S. seems arbitrary. Drawn by power seekers and maintained, physically and psychologically, to keep Indigenous people from acknowledging our commonality. Which begs the question, why are colonizers so afraid of Indigenous people allying with each other across Turtle Island?

I'm reminded of the various tribal confederacies in North America who once attempted to unify Indigenous people, and the most famous in the U.S. was Tecumseh's Confederacy (Chief Tecumseh Urges Native Americans to Unite), which ultimately lead to siding with European allies in the struggle for retaining control of traditional lands. Similarly, there were alliances on the Southern Plains of North America, where Kiowas allied with Comanches and held back westward expansion for 100 years (Oklahoma Historical Society). Once they extended their alliance to include the Cheyenne and Arapaho tribes, a confederacy of Indigenous tribes dominated the Southern Plains of North America.

Needless to say, the circumstances that drove Indigenous people in the past are radically different than our need to unify today. Where land base was a primary mode of those alliances, today we are tasked with protecting not only a way of life but more importantly how that way of life is inextricably tied to land based practices. Moreover, to stand against the contamination of earth, air, and water--the three elements needed for human survival. Our plight to unify isn't strictly for the benefit of Indigenous peoples, but for all people to survive and live healthy lives. The environmental war being waged against Indigenous people in Canada is the same war being waged against Indigenous people in Mexico. Whether we're looking north or south, we, as Indigenous people in the United States, have allies in both directions. Why would we limit ourselves to myopic, hyper local identities? Because of a language barrier? Our ancestors developed sign languages to navigate dozens of tribal languages. So we can't beat one colonial language? We're as smart as our ancestors and have the intelligence to know how outdated people lock themselves into identities based in violence. We're smart enough to unfollow and unfriend and silence those seeking to keep Indigenous people from unifying. Outdated practices will only serve to keep Indigenous people fighting with each other, where neo-tribal politics can see the unifying history--how Native people were not only forced to flee into Canada, but to also flee into Mexico.

And now it's time for a return.

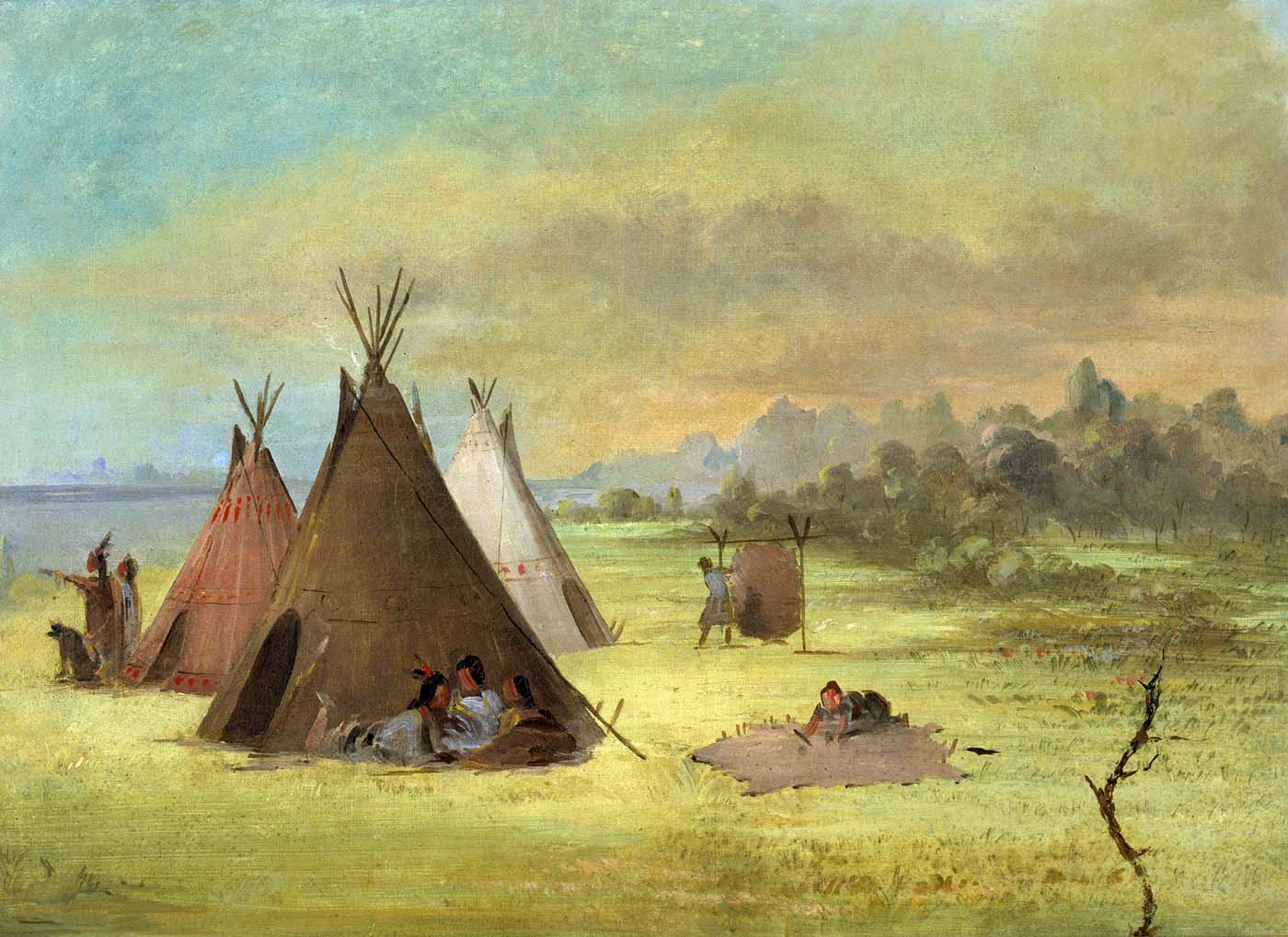

(Images were borrowed from The Canadian Encyclopedia, Pinterest, and Facebook.)

How to Smudge with Sage & Native American Customs for Prayer

I've had several people inquire about practices and customs associated with smudging. I decided to cleanse myself today so I thought I'd make a short video on rituals I've learned over the years. This is by no means anything dogmatic. These are just methods that I've learned over the years. I'm Kiowa and Cherokee, and I've incorporated practices between both cultures and lessons I've learned personally through doing this routinely that work for me.I hope you enjoy the video. Please feel free to share with as many folks as you like, and if you have questions reach out to me in the comments. Wa'do, have a blessed day, and if you're interested in Native American fiction please support my debut novel, CALLING FOR A BLANKET DANCE: Bookshop, Amazon, B&N, IndieBound.https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Z3GGFIfJY0Q

Native American Cuisine in Kiowa Literary Thematics

Exploring culture through foods is nothing new to the literary world. Likewise, it's not new to Native American literature. While we in the literary field know this to be true there is still very little exploration of the topic in thematic terms. How can traditional food and customs associated with consumption of those foods enhance the greater theme of a piece?Those of you reading this post to learn how to make Native American food may be asking, "What is Native American cuisine?" You'll have to search a little further to find out details on cooking Native American food, but I'll give you a little sample of what may constitute Native American cuisine in this article. For further elaboration on the topic of Native American cuisine check out: Foods of the Southwest Indian Nations by Lois Ellen Frank. She taught my ethnobotany course at the Institute of American Indian Arts and knows what she's talking about. Plus she's Kiowa so that puts her on my radar. There are a host of other options you can find on Amazon as well. Diabetes is a serious issue among Native peoples so I'm going to link a vital source for healthy eating here: Click Here!Back when I was a young guy "tearing it" on the Southern Plains of Oklahoma meatpies were indicative of KCA culture (Kiowa, Comanche, and Apache). It was a localized food specific to a certain geographic area. Today, using meatpies as a Kiowa artist, it can be applied for generational specificity in that it "was" localized, and now tribes across Oklahoma and other parts of Native America have latched onto it as a "cultural food." Living in Tahlequah today I've found many Cherokees making meatpies, but when I was growing up in Tahlequah as a child meatpies weren't in the community so I would dream of trips back to Lawton, Oklahoma (KCA country) where I could get my hands on a meatpie. Oh, the diaspora!![]() In my short story, Our Dance, you'll find in the second paragraph of the story the narrator describe receiving his Kiowa per cap, his ahongiah, (which was federally dispersed money where the Kiowa tribe allocated a financial disbursement between all tribal members), as "we both tore into those envelopes faster than the last meatpie on a plate." In the juxtaposition of receiving money alongside a cultural food like meatpies, we deduce the equal desperation in which both were acquired, and how each--meatpie and money--have become an appropriated substance for cultural survival.Meatpies are made from the combination of fry bread and meat. More or less a meat-stuffed piece of fry bread. Fry bread is commonly understood as a cultural food, but it's not traditional, meaning our ancestors didn't make fry bread prior to contact by Western peoples. It became a consistent part of our cultural foods when the U.S. government distributed food rations to tribes (we commonly refer to them as commodities or "commods" for slang). Because meatpies are basically fry bread with meat inside, they have also become a survival food for Kiowa, Comanche, and Apache people in southern Oklahoma (further out now due to diasporic conditions).When the narrator of my story, Our Dance, describes going for money the same as going for "the last meatpie on the plate," it speaks to the creative and critical thinking skills applied by Kiowa people to take something and appropriate it for cultural survival. In essence the story's title, Our Dance, is the dance of survival, like meatpies, like receiving per cap, like bonding with the community. To further connect this thematic for the reader, the quote at the onset of the story by James Auchiah, “Kiowa Five” artist (now Kiowa Six) and Chief Satanta’s grandson, reads, “We Kiowa are old, but we dance.” It is the dance of survival beginning with the narrator's ancestors and carrying into his present community which dictates his use of cultural foods for survival, and subsequently my use of culture, food, and customs to connect the thematic dots for my readers.

In my short story, Our Dance, you'll find in the second paragraph of the story the narrator describe receiving his Kiowa per cap, his ahongiah, (which was federally dispersed money where the Kiowa tribe allocated a financial disbursement between all tribal members), as "we both tore into those envelopes faster than the last meatpie on a plate." In the juxtaposition of receiving money alongside a cultural food like meatpies, we deduce the equal desperation in which both were acquired, and how each--meatpie and money--have become an appropriated substance for cultural survival.Meatpies are made from the combination of fry bread and meat. More or less a meat-stuffed piece of fry bread. Fry bread is commonly understood as a cultural food, but it's not traditional, meaning our ancestors didn't make fry bread prior to contact by Western peoples. It became a consistent part of our cultural foods when the U.S. government distributed food rations to tribes (we commonly refer to them as commodities or "commods" for slang). Because meatpies are basically fry bread with meat inside, they have also become a survival food for Kiowa, Comanche, and Apache people in southern Oklahoma (further out now due to diasporic conditions).When the narrator of my story, Our Dance, describes going for money the same as going for "the last meatpie on the plate," it speaks to the creative and critical thinking skills applied by Kiowa people to take something and appropriate it for cultural survival. In essence the story's title, Our Dance, is the dance of survival, like meatpies, like receiving per cap, like bonding with the community. To further connect this thematic for the reader, the quote at the onset of the story by James Auchiah, “Kiowa Five” artist (now Kiowa Six) and Chief Satanta’s grandson, reads, “We Kiowa are old, but we dance.” It is the dance of survival beginning with the narrator's ancestors and carrying into his present community which dictates his use of cultural foods for survival, and subsequently my use of culture, food, and customs to connect the thematic dots for my readers.

Hyperlocal Advocacy in Native American Literature

I've been promoting my writing on my Twitter account for a few months now. Slowly but surely I'm getting more and more engagement and I'm nearing the cusp of 9K followers, and hoping to hit the 10K plus realm within a week or so. One of my followers, and now a tried a true fan, read through each of my short stories and came up with an interesting descriptor of my writing: hyperlocal. As soon as I read the phrase it hit me as so succinct I could not help but become fascinated. This term may have been utilized in creative circles for some time. I'm not sure. But its my first time engaging with it. Largely, I'm interested in the description because of how accurately it describes my writing.In my bio you'll read how I've captured my writing up to this point, and I've said things like "regionally specific" and focusing on Kiowa and Cherokee communities like Lawton (Kiowa) and Tahlequah (Cherokee). Now those from Oklahoma will quickly point out how Lawton is Comanche Nation central, and they'd be hypothetically correct. But geographically I argue these boundaries are not fixed and never have been.I'd say Kiowa, Comanche, and Apache (KCA) nomadic range in contemporary society is typically between OKC and Lawton, but you'll find our scouting parties traveling further out (all this is a cultural rehearsal in a historical context based in nomadic practices that have been a part of our cultures for hundreds if not thousands of years). You'd actually have to have grown up inside a Kiowa, Comanche, and/or Apache family to fully understand this nuanced "roaming" aspect of our culture. Once you understand, you can see how our gourd dance culture is so deeply imbedded in other tribal practices across the United States. An example? Our, Kiowa and Comanche, gourd dances have widespread practice within Navajo communities of New Mexico and Arizona, but other tribes in the United States as well.

As soon as I read the phrase it hit me as so succinct I could not help but become fascinated. This term may have been utilized in creative circles for some time. I'm not sure. But its my first time engaging with it. Largely, I'm interested in the description because of how accurately it describes my writing.In my bio you'll read how I've captured my writing up to this point, and I've said things like "regionally specific" and focusing on Kiowa and Cherokee communities like Lawton (Kiowa) and Tahlequah (Cherokee). Now those from Oklahoma will quickly point out how Lawton is Comanche Nation central, and they'd be hypothetically correct. But geographically I argue these boundaries are not fixed and never have been.I'd say Kiowa, Comanche, and Apache (KCA) nomadic range in contemporary society is typically between OKC and Lawton, but you'll find our scouting parties traveling further out (all this is a cultural rehearsal in a historical context based in nomadic practices that have been a part of our cultures for hundreds if not thousands of years). You'd actually have to have grown up inside a Kiowa, Comanche, and/or Apache family to fully understand this nuanced "roaming" aspect of our culture. Once you understand, you can see how our gourd dance culture is so deeply imbedded in other tribal practices across the United States. An example? Our, Kiowa and Comanche, gourd dances have widespread practice within Navajo communities of New Mexico and Arizona, but other tribes in the United States as well. This is to give you a sense of how aware I am of Kiowa habits and behaviors, but not only Kiowa also Cherokee since I've had the fortunate circumstance of growing up within both cultures and moving back and forth between Lawton and Tahlequah in various forms throughout my life. These landscapes (Southern Plains and Ozark Hills) are not only imprinted in my memory, but my fiction as well.When this individual from Twitter mentioned "hyperlocal" as a description of my writing, I started to think about these nuanced cultural practices, behaviors, and perspectives, and how it was born from "writing what I know." And I think there can a tremendous benefit to this form of regionalism. What I do isn't any different in theory to Faulkner's depiction of the South during his time.Readers crave escapism. And at the onset of using a term like escapism there is an immediate interpretation of needing "to escape from reality" as a coping mechanism. But I would argue readers are more interested in engaging with creative work to find a reflection of themselves so as to examine their own presence on this planet. They are interested in growth, whether this is a conscious or subconscious effort is an argument for another nerdy post, but all in all readers are looking for "safe" ways to examine their own condition. It is through compare and contrast we find new ways to behave. Sometimes these new behaviors are better and sometimes they are destructive. But we will survive by any and all creative means, so I believe readers are subconsciously looking for validation and simultaneously seeking new ways of survival.The hyperlocal is a great way to find a place to escape, and to find a different culture to observe so as to better understand our own behavior. For me, this dynamic is on the surface. I love change, and stagnation is deadly. I want to become different. I want growth. But for others there may be a subconscious reason for engaging with the hyperlocal. The writing will resonate with them and they can't pinpoint why--just that there is something appealing about it.The means I use in which to tap into this dynamic? Is hyperlocal.

This is to give you a sense of how aware I am of Kiowa habits and behaviors, but not only Kiowa also Cherokee since I've had the fortunate circumstance of growing up within both cultures and moving back and forth between Lawton and Tahlequah in various forms throughout my life. These landscapes (Southern Plains and Ozark Hills) are not only imprinted in my memory, but my fiction as well.When this individual from Twitter mentioned "hyperlocal" as a description of my writing, I started to think about these nuanced cultural practices, behaviors, and perspectives, and how it was born from "writing what I know." And I think there can a tremendous benefit to this form of regionalism. What I do isn't any different in theory to Faulkner's depiction of the South during his time.Readers crave escapism. And at the onset of using a term like escapism there is an immediate interpretation of needing "to escape from reality" as a coping mechanism. But I would argue readers are more interested in engaging with creative work to find a reflection of themselves so as to examine their own presence on this planet. They are interested in growth, whether this is a conscious or subconscious effort is an argument for another nerdy post, but all in all readers are looking for "safe" ways to examine their own condition. It is through compare and contrast we find new ways to behave. Sometimes these new behaviors are better and sometimes they are destructive. But we will survive by any and all creative means, so I believe readers are subconsciously looking for validation and simultaneously seeking new ways of survival.The hyperlocal is a great way to find a place to escape, and to find a different culture to observe so as to better understand our own behavior. For me, this dynamic is on the surface. I love change, and stagnation is deadly. I want to become different. I want growth. But for others there may be a subconscious reason for engaging with the hyperlocal. The writing will resonate with them and they can't pinpoint why--just that there is something appealing about it.The means I use in which to tap into this dynamic? Is hyperlocal.

Support a Native owned Etsy shop, Allies United, where I offer unique merch for allies of social justice movements, like MMIW, Native Lives Matter and Black Lives Matter. Take a look inside my Etsy shop here: etsy.com/shop/AlliesUnited.

(Works Cited: Both images were borrowed from wikimedia)

When Girard Married Freire: The Scapegoat Rides Praxis into the Sunset

It's about to get real nerdy in here. Turn around and walk away. Don't read any further. If you pass beyond this point of warning then all consequences will be your own and you will be held accountable. So... Do the right thing. Just stop reading now.If you're still with me, sucks to be you. But you were warned. What I'm about to do is elaborate on Paulo Freire's praxis by using Rene Girard's mimetic theory, See? I told it was getting nerdy up in this piece.Girard is the lens. Freire's praxis is the subject of study. If you've read any of my previous posts you'll have an understanding of Girard's mimetic theory. He basically, to make a point quickly, states mimesis is the "fuel" that creates culture, and the first pit stop is scapegoating. So when we're stressed, we scapegoat. We find someone to blame, we blame the person or people for all our problems (even if it's irrational), and then we either banish the scapegoat or kill the scapegoat (in either scenario we then idolize the scapegoat). This sequence makes us feel "all better," like momma patting us on the head when we have a booboo. Girard argues in the ritualization of scapegoating we create culture. We create customs, rituals, practices, celebrations, feasts, whatever you want to call it, we create culture through this production.If we use a major religion as way to look into Girard's point, such as Christianity, Girard would say Jesus and Satan are both scapegoats. One scapegoat "saves people," while the other scapegoat "seeks revenge," but both scapegoats, ultimately, keep people from fighting each other.Now Girard focuses on mimetic rivalry as his main point, and scapegoating is the only thing that stops mimetic rivalry. In other words, when "in fighting" occurs, we find a scapegoat so "we can all just get along." Mimesis is a nerdy way to say "monkey see, monkey do."In a Native context, we can say the current paradigm of colonization has set in motion a mimesis based in conquest (and all the paracolonial conditions it comes with). So this is where I bring in Friere. Friere's praxis is a heavily used (almost over used) term to show the societal "flip" when the oppressed minority reclaims power (education) from the colonizer and subsequently finds herself at a crossroads. "Will I use my power (education) to become a savior or the devil?" we might imagine a conscientious minority asking. This is a big subject of debate for a number of reasons. From my vantage point, it looks like the #1 reason is "the dominant culture doesn't want to lose power and become the victim of revenge." If anything hurts the dominant cultures' feelings, then we have to talk it to death as they can release all their anxiety onto the world. Take a chill pill papa smurf, this narrative is about Smurfette.Ultimately, the question becomes: Has the oppressed been infected with the disease of power by the oppressor? Do the oppressed not know where they end and the oppressor begins? If Girard had anything to say on this Native discourse (he's dead so good luck with that), then he would argue Natives are scapegoats returned, either back from the dead or back from banishment, like Jesus and Satan.So have I seen evidence of how the "flip" is going to play out? On a day to day basis, it looks like Natives love some power and we abuse each other with it (which is what the colonizer designed to happen, aka colonial mimesis). But as far as organizing that power to exact revenge against the dominant culture, I haven't seen it. We've all seen Natives function as "savior," when NODAPL attempted to stand up for clean water rights for everyone. On a macro level, Natives tend to do what's the best for everyone, which is why most of us are liberal in politics. On the micro level, Natives tend to do what's best for themselves, which is why most of us are socially conservative.So there it is: in all it's nerdery. Do you think Girard's scapegoat theory is applicable to Frerie's praxis? How do you think this will play out in a Native context?

If Girard had anything to say on this Native discourse (he's dead so good luck with that), then he would argue Natives are scapegoats returned, either back from the dead or back from banishment, like Jesus and Satan.So have I seen evidence of how the "flip" is going to play out? On a day to day basis, it looks like Natives love some power and we abuse each other with it (which is what the colonizer designed to happen, aka colonial mimesis). But as far as organizing that power to exact revenge against the dominant culture, I haven't seen it. We've all seen Natives function as "savior," when NODAPL attempted to stand up for clean water rights for everyone. On a macro level, Natives tend to do what's the best for everyone, which is why most of us are liberal in politics. On the micro level, Natives tend to do what's best for themselves, which is why most of us are socially conservative.So there it is: in all it's nerdery. Do you think Girard's scapegoat theory is applicable to Frerie's praxis? How do you think this will play out in a Native context?

Support a Native owned Etsy shop, Allies United, where I offer unique merch for allies of social justice movements, like MMIW, Native Lives Matter and Black Lives Matter. Take a look inside my Etsy shop here: etsy.com/shop/AlliesUnited.

(Disclaimer, aka Works Cited: The image was borrowed from www.hediedformygrins.blogspot.com)