U.S. Southern Culture: Where are the Native American Authors?

Since Tahlequah, Oklahoma is only 30 miles from the Arkansas border, we relate mostly to U.S. Southern culture. Why do I mention my hometown? It's not only the place where I live, work, and raise my family. It's also home to two Cherokee tribal governments: Cherokee Nation and the United Keetoowah Band of Cherokees. I personally work for Cherokee Nation in the Indian Child Welfare Department. Additionally, the third Cherokee government is the Eastern Band of Cherokees in North Carolina. All this to say, Cherokees are the largest federally recognized tribe in the United States and our governments are historically situated in the South. So why don't we exist in the canon of Southern literature?

It looks like the American system has made us invisible once again. It amazes me how hard folks work to keep the "pristine myth" alive. While we are the smallest minority in the U.S., we are here. Don't believe the lies. The land is not vacant. There are Indigenous people here and we've been here since time immemorial. We drive the same highways you drive, and often climb the same ladders. So there's not a lack of Natives writing from the South. What's missing is the amount of attention we receive.

If I were to ask you, who is the quintessential Native American author from the South? Does anyone come to mind? Now don't go running to Google! That's cheating. I can name several contemporary Native American authors with Southern roots, but I have a Master's Degree in English with a concentration in Native American Literature from the University of Oklahoma. If I didn't readily know any names that'd be a problem. But most American readers don't know. Some might mention Joy Harjo because she was the U.S. Poet Laureate in recent years.

As far as fiction writers, there's Leanne Howe, Annette Saunooke Clapsaddle, and Kelli Jo Ford. There are also contemporary poets, like Sy Hoahwah and Santee Fraizer. Those are off the top of my head. More names will come to me later. Historically, there's no one with more publications than Robert J. Conley, who was not only an enrolled member of the Keetoowah Band of Cherokees but also wrote novel after novel about Cherokees in traditionally Southern environments. He not only wrote about Cherokee historical figures but also depicted the removal of Cherokees from North Carolina in his novel Mountain Windsong. While much of his writing was historical fiction, he won three Spur Awards in the Western genre. Conley was someone who should've received more recognition for his contributions to Southern literature. Maybe we could've honored him in the same way we honored Lee, Hurston, and Faulkner.

I'd like to commend the publishing industry for recognizing when there is a societal discrepancy, like lack of representation. In recent years there has been tremendous gains in this area. There are more BIPOC authors right now than there has ever been in American history. I'd also like to ask the publishing industry to consider the biggest issue facing Native Americans today: invisibility. We are the smallest minority in the U.S. with some of the highest disparity rates. Our communities are doing phenomenal work to end intergenerational trauma. Native people are resilient, hardworking, and proud. Give Southern Natives the opportunity to showcase our tenacity and strength. Recognize our contributions to the publishing industry. The canon of Southern literature needs Native voices--voices that not only advocate for tribally specific customs but can also represent historically targeted communities with a critical eye and genuine compassion.

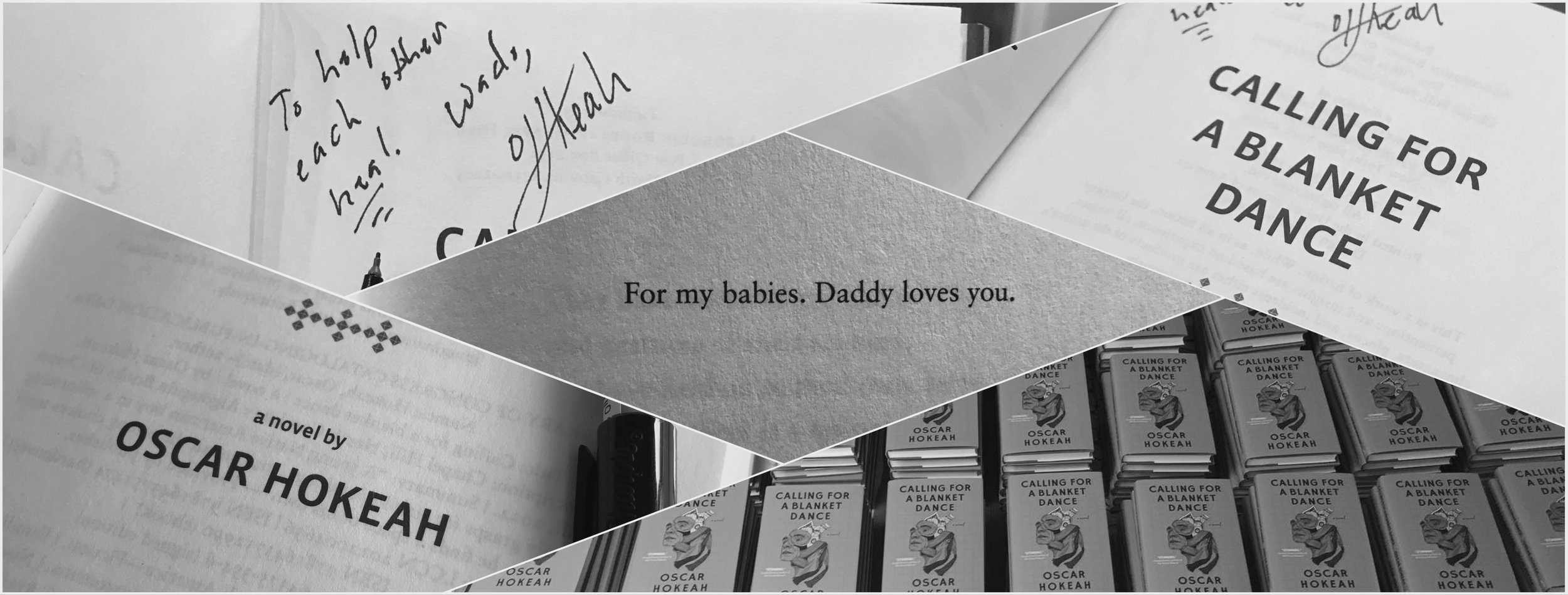

Debut Novel 14 Years of Ups and Downs: How CALLING FOR A BLANKET DANCE Survived, Endured, and Finally Came to Being

I'm always drawn to these stories. Of the writer who wrote for decades to finally find her way onto a bookshelf. I'm drawn to them because I feel for what the writer has endured and the level of gratitude that comes along with it. It's rough out there. We're all tough. You can't endure the writing process without thickening your hide with a multitude of scars. There are many talented writers. When it all comes together, when your hard work finally meets opportunity, you can't help but find yourself in a gracious meditation on the trials and tribulations of creating your work of art.

I'd like to start this with an homage to the educators. You see back before my entrance into literary writing, I wanted to be the Native Stephen King but I was also growing further away from the horror genre. During this period in my late 20s, I luckily found myself accepted into the Institute of American Indian Arts (IAIA) in Santa Fe, New Mexico. This was where I delved deep into literary genre's themes around social justice. I also met my mentors, Evelina Zuni Lucero and Stephen Wall, at IAIA. Evelina was the Head of Creative Writing, and Stephen Wall was the Head of Indigenous Liberal Studies. Little did I know at the time that I'd walk away three years later holding a BFA in Creative Writing with a minor in Indigenous Liberal Arts. I'm indebted to Evelina and Stephen for the leadership, guidance, and willingness to mentor a stubborn and often egotistical young man.

It was during my time at IAIA that I developed the earliest chapters of my debut, CALLING FOR A BLANKET DANCE. I wrote a story titled, Got Per Cap?, in 2008 and this was where my Kiowa community voice came out. The story was later published in American Short Fiction as "Our Day," and then eventually I changed the title to "Our Dance." Now the story is the fifth chapter in the debut, which is titled "Quinton Quoetone (1993)." Soon after developing my Kiowa voice for the page, I then began developing my Cherokee voice, and this came to fruition the following year, 2009, when I wrote a story called "Time Like Masks." This story would eventually be published in South Dakota Review, and is now the third chapter in my debut, titled "Hayes Shade (1986)."

"Psychologically, I couldn't even slide a flash drive into my computer for the purposes of writing another story, chapter, novel."

~ Oscar Hokeah ~

It was the process of developing these two stories that began a life long effort to disrupt the perception of Native American peoples as being a single homogeneous group. Since I grew up between Kiowa and Cherokee communities in Oklahoma, I knew first hand about the similarities and beautiful differences between tribes. I also knew about the ugly contention between these two communities--slights, judgments, and stereotypes all. I felt like I could show readers in subtle and obvious ways how these dynamics play out. How we as Indigenous peoples share a common history of colonial violence, which pulls us together, and at the same time how each tribe has beautiful and unique qualities to be honored and cherished.

By the time I graduated from IAIA in 2009 and went on to the University of Oklahoma in 2010, I had my ego bruised enough times to be humbled by the creative writing process. There is no better way to condition yourself to humility than pouring yourself onto a page and receiving the harsh realities of what is and what isn't. In 2010, I had a sense of my direction as a writer. I was already calling myself a regionalist writer. In fact, I used the two stories mentioned above in my admissions paperwork to the University of Oklahoma (OU), and it was this very dynamic of seeking to disrupt the perception of Natives being a homogeneous group that had me accepted in the Master's Program.

It was at OU that I found my next mentor, Dr. Geary Hobson. I had entered the Master's Program under the Creative Writing program, but quickly found myself hitting a writer's block. This would begin years and years of self-doubt and self-criticism that would cripple my ability to write. While the two stories mentioned above were both published (both before I obtained a Master's Degree), I received harsh criticism that I felt was more of an attack on my drive to become a published author. One thing I've learned is that in writing programs we find our most cherished mentors, but we also find our most ambition detractors. For every person hoping for our success, there are a dozen others wishing for our failure. I quickly stopped writing. Psychologically, I couldn't even slide a flash drive into my computer for the purposes of writing another story, chapter, novel. I thought of myself as failure who didn't truly see his pathway to publication, and more of a delusional novice with perpetual misgivings. Eventually, I switched to a concentration in Native American Literature, and this is where I found Dr. Hobson. He was kind and considerate and took me under his wing, talking to me for long periods of time and sharing some of his secrets to staying in the creative writing space.

"Suddenly, the last strand weaved itself into place. I had figured it out. This was a decolonization narrative and the main character was healing through familial love and cultural grace."

~ Oscar Hokeah ~

It wasn't until after I graduated from OU in 2012 that I found myself writing again. It had been three years at this point. The stories I mentioned above were written in 2008 and 2009, and then I finally started to write again in 2012. I wrote the first draft of one story that would later be titled "Paper Towels." Slowly, I wrote a story here and a story there (all first drafts), and then I started to revise, slowly again, until I had a good collection together. By 2014, I had my first book and titled it: Reflections on the Water. The collection centered a male character who had similar traits as his mother. Basically it was a compare and contrast. I remember sending out queries to agents and they all came back rejected. But I kept going. I submitted some of the stories, like the one titled "Paper Towels," to literary magazines. Again, I received rejection after rejection. None of the stories were getting picked up, and the agents weren't responding to the collection of stories. Finally one agent responded and asked for 50 pages, but after I sent the 50 pages I never heard back again--not even to get a firm rejection. So I gave up again. It was pointless. Why was I writing? No one was interested.

One year and one divorce later, I found myself back in my hometown of Tahlequah, Oklahoma in 2015. Having just left a job that was spiritually grueling and traumatizing for reasons I'll not mention here, I decided I was going to write a novel about the experience. This one wasn't going to be a novel-in-stories like my last defeat. This one was going to be a full length novel about enduring the hardships at this specific place of work. I've mentioned this experience on previous posts, but my brand of writing is what folks might call "semi-autobiographical fiction." It's fiction, but it's closely drawn from my personal experiences or experiences of friends and family. I was taught "write what you know" at IAIA, and I took it to heart. So I spent the next year writing this novel. I wrote a complete first draft and then sat it aside in 2016.

Then I received an email from my old mentor, Dr. Hobson. He asked me what I was working on and I had mentioned the novel about my "workplace tribulations." But it was this simple and generous question that made me start thinking about the collection of stories that didn't quite make it. So two years later I decided to slide the flash drive into the computer and take a look at these stories again. I figured I had nothing to lose so I decided to tear it apart, to look for a different story line, to find a better angle. I discarded some stories and kept others. It was a little triggering. My self-doubt increased again, but I kept at it. I kept looking at the stories and searching for something that might work as a book. After months and months of stepping away from the stories and then opening them back up, I finally saw it. This wasn't a compare and contrast novel. It was a transformation narrative. The central figure wasn't a reflection of his mother, but instead he was an entire ecosystem--and this ecosystem was his family. I saw the thread where the main character was highly aggressive when he was younger and then eventually purged his aggression. So why did he transform? Suddenly, the last strand weaved itself into place. I had figured it out. This was a decolonization narrative and the main character was healing through familial love and cultural grace.

It was 2017 when I started writing new stories, started adding new characters, new family members, and the ecosystem just grew and grew. Soon I could see this one character from a multitude of angles because every family member had a different view point of his life. Literary fiction is character driven fiction. The greatest compliment a literary writer can get is that "these characters are real and alive!" With the chorus of stories, the main character was more alive than he had ever been. So it was somewhere in the middle of 2018 when I learned of #DVpit on Twitter. It was a pitch event for "diverse voices," and I decided I was going to give my new collection in stories a shot. For two months, I wrote and rewrote a tweet-sized pitch. Then the day of the #DVpit pitch event arrived, and I started to post...post and watch...watch and post. To my surprise, the one and only Beth Phelan retweeted my pitch with eye emojis. So five different agents clicked on my tweet. I couldn't believe it.

"I was a #DVpit success story."

~ Oscar Hokeah ~

Long story short, I signed with Allie Levick of Writers House. I was a #DVpit success story. It worked. I couldn't believe my luck, and my confidence shot through the roof. So when Allie came to me and said, "We're going to need to add about 30,000 more words," I didn't flinch. I said, "I can do it," and I completely believed in myself. And over the next few months I did exactly that. This was when Vincent Geimausaddle, Opbee Geimausaddle, and Araceli Chavez were born. I added new family members and strengthened the ecosystem that we all now know as Ever Geimausaddle. So Allie and I worked over 18 months tightening up the novel and getting it ready for publishers. It was now late 2019 and we came to the final moments of revision. Then early 2020 came and we started pitching to publishers. And we all remember what happened in early 2020: COVID. So the exact same time Covid hit the United States and shut everything down, I negotiated terms with my publisher, Algonquin Books. Later that summer the contracts were signed. It was official. I was going to be a published author.

Now the story doesn't stop there. As all those published writers know: there is the process of revision with the editor. I started working with Kathy Pories and she did a phenomenal job of slicing and dicing. She knew exactly what to say to get me to take the novel to the next level. It was motivating. She asked me to cut certain things that made the novel exactly what I was hoping it'd become. Her talent for seeing the true essence of a story is amazing. Sometimes it's just rearranging small dynamics and cutting the tiniest pieces that brings a character to an even brighter spirit. By time Kathy and I were finished, we had transformed a novel-in-stories into a full length novel. It was awesome to see and a great learning opportunity. I can say with absolute certainty that I'm a better writer for working with Kathy. I'll be forever in her debt.

So it was the end of 2021 and Kathy and I finished with the last of the last copy edits. Finally, the book was complete and fully packaged and ready to go. Now, it was time for getting the word out. Writing is the hard part and it was long and arduous, but we can't underestimate the value of marketing. Next, I began reworking a pitch that I thought I had a handle on. I soon realized that every time I was asked the dreaded question, "So what's your book about?," I had a different response. I didn't know why. Through the events put together by the marketing team, I was given the space to work and rework a succinct pitch. I've had to learn what to say at the beginning of my response to get my brain to funnel toward the center of the novel. What I've learned is that there is always refining to do, and all this refinement started 14 years ago. My debut, CALLING FOR A BLANKET DANCE, landed on bookshelves on July 26, 2022. And it's been a whole other learning experience in my debut year. So stay tight to my blog, and sometime in the not-so-distant-future I'll recount the trials and tribulations of my book's first year in the world.

Tips, Tricks, and Doodads: Watch Out for Exposition! It's a Plot Killer!

I can't tell you how much I hate exposition. I know hate is a strong word. But it kills my plot. There I am plotting along. Happy as can be. I love plot. Plotting along is my favorite thing to do. Then here comes "necessary info." And in order to do my favorite thing I must engage with the thing I dislike the most.

The type of exposition I'm referring to is most commonly known as the "info dump." It's necessary information--often backstory--about characters that ultimately keeps the plot moving forward. So if you're reading about someone traveling to Tahlequah, Oklahoma for the Cherokee National Holiday, where they are about to reconnect with a long lost Cherokee sibling, you're going to need to know what first set them on this trajectory. The why and how is the plot. But nobody likes the what. It's all about the how. Everybody loves the how. How do I know this? Because how is the reason why I hate the what.

All kidding aside, I tend to minimize this type of exposition. Sometimes it involves introducing the characters in the novel. Readers must know all the major players. I tend to want to put this at the beginning of the novel so it doesn't disrupt my plot at critical moments later in the story line. I feel like it's early in the novel where readers have the most patience for this type of information. The "who's present" and why and how they effect the main character. It's like the main character is the sun, and the supporting cast are the planets in a solar system. Sometimes explaining gravitational pull is like pulling teeth. I know I'm mixing metaphors here but that's what exposition does to me. It makes me crazy.

Where was I? Oh yeah, I try to get away with as little exposition as possible. On a first draft, I info dump. I get it all out there. Then I start to whittle it away as I move through the revision phase. What's the smallest amount of exposition I can use without losing the "necessary info?" I want to start the reader in the middle of the action, and once I have the plot moving forward I don't want them to pause. Exposition makes them pause. So by reducing the amount of back story I can usually hide it with voice, using my personal colloquial method of capturing story on the page. If there's too much exposition, it's hard to hide it from the reader.

There are a number of other suggestions out there about handling exposition, like a character asking questions or spreading it out in small pieces, which are great and I use those from time to time as well. Mostly, I do what I mentioned above. I cut it down in size and flavor it with my writing voice. Typically, it works great but it can take many pass-throughs or revisions in order for it to feel like I've gotten it right. I'm a bit meticulous when it comes to this. Since it's such a hard disruption of plot, my perfectionism kicks in for the purpose of smoothing out the hard edges of exposition. I want to read through it as easily as I read through the rest of the novel.

If you have any suggestions, or methods that work best for your writing, I'd love to hear about it. How do you get through the "necessary info dump?"

Why I Vanished from Social Media

I wish I could say there was only one reason. But there was definitely a primary reason. The last two months have been a little rough for my family. My little sister had a major stroke. For those of you who've had a loved one go through this you'll understand perfectly what I mean. It's sudden, unexpected, and unfortunately my sister didn't make it to the hospital in time to get the medication that would have saved her from the more severe damage. So there we were: a family in turmoil having to make major decisions regarding my sister's life.

Truly, social media had become habitual chaos. Posting, commenting, liking, sharing across four--sometimes five--platforms can be a lot. When real life happens, suddenly it can appear to be a little absurd. With the challenges of new circumstances, clicking on a social media icon was too difficult. My little sister's life was forever altered, and there was a window when we weren't sure if she would survive. So eventually, I went onto all my social media sites and just deleted them. One after the other and in a matter of a seconds they were all gone. And there was something empowering about that moment. I knew what mattered most and I was going to give it my full attention.

There was a part of me that felt a little guilty. I had released my debut novel in late July and had been plugging away on social media to promote the book. I met many great folks. Sometimes I wished I had that back again. The playful comments and genuine connections. There are a ton of kind and generous people out there. Right now my days are filled with juggling my kids' needs, helping with my little sister, and continuing to serve in Indian Child Welfare. We just finished Cherokee Nation's Angel Project where we gave Christmas gifts to 2,800 Cherokee children in need. We made Christmas a little brighter for some of our most impoverished citizens. I also got to spend quality time with my daughters, and worked with my little sister to help her speak again. It's been busy and trying in profound ways.

I'm grateful, and I've been good about being grateful, but maybe I'm a little more grateful these days. Maybe sometime in the future I'll start my social media back up again. If a new normal ever sets in. For the time being, I'll be posting here on my blog. It's much more straight forward and easy to engage with. Right now I need to keep my life simple to get through.

In Defense of Peripheral Narration: Fitzgerald Vs Hokeah in a Battle of Class, POV, and Power

Have you heard of a book called The Great Gatsby? It's written by F. Scott Fitzgerald. Most folks read it in high school. I didn't make it to high school (the last grade I completed was the sixth grade) so I didn't read it until I was an adult (after I went on to obtain a Master's Degree). If you remember, the novel is told by a character, Nick Carraway, about another character, Jay Gatsby. The reason I'm bringing up this particular book is two fold: (1) It's well known, and (2) it's a popular example of peripheral narration, where one character tells the story of another character. Don't worry this is not a rehearsal of Fitzgerald's novel. Instead it's an allusion to mine.

If I were to make a comparison between The Great Gatsby and my debut novel, Calling for a Blanket Dance, I'd argue it takes peripheral narration and amplifies it. Why? I enhance it with polyvocality. Both books are short reads that pack a big punch, yes. But we, Fitzgerald and I, operate from opposite ends of the class spectrum. As you probably know, The Great Gatsby is about the wealthy and critiques the American Dream by showcasing the underbelly of the uber-rich, where Calling for a Blanket Dance is an homage to the working class, who aren't trying to stratify a system but simply want to live without becoming victims to a movable standard. The Great Gatsby is to the wealthy what Calling for a Blanket Dance is to the working poor.

“There are only the pursued, the pursuing, the busy and the tired.” ― F. Scott Fitzgerald,The Great Gatsby

All that aside, let's think about the periphery. If we were in a creative writing class, I'd probably give you reasons why an author, such as myself and "old boy" Fitzgerald, would employ it as a technique. These reasons tend to be somewhat obvious, like the main character might have a secret, she or he might die during the course of the novel, they could be unlikable and therefore not relatable, and/or each story might be more important to the narrator(s) than it is to the main character. But this is not a creative writing class so I'll not go on about those.

What I will address is the richness of peripheral narration when doubly executed with polyvocality. What happens when 11 different people tell a story about you? If they were coworkers, we'd probably get the down and dirty about your shady-ass past and how you're not as angelic as you might think you are. If it's your family, then we'll get something a little more diverse, a little softness to go along with the prickly. Bittersweet, if you will. And I'll argue here that we'd get more depth about you as a person from your family than we would from you. Using peripheral narration mixed with polyvocality gives readers a much richer and deeper understanding of a main character.

“Let us learn to show our friendship for a man when he is alive and not after he is dead.” ― F. Scott Fitzgerald, The Great Gatsby

Ultimately, it gives us more than the typical drama triangle (villain, victim, hero). Instead we move away from Western traditions in literature and step a little closer toward Indigenous ideology, like shaping an entire novel on traditional Kiowa and Comanche customs (say a Blanket Dance, maybe). Here the community has agency--not the individual--where a collective center from a tribally specific and historically targeted community wrap around each other in support, healing, and decolonization. Where we acknowledge how we are shaped by the people who love us the hardest. Moreover, where a chorus of voices sing in rhythm with a single thundering drum, reverberating out and across the planet to announce: our power is back.

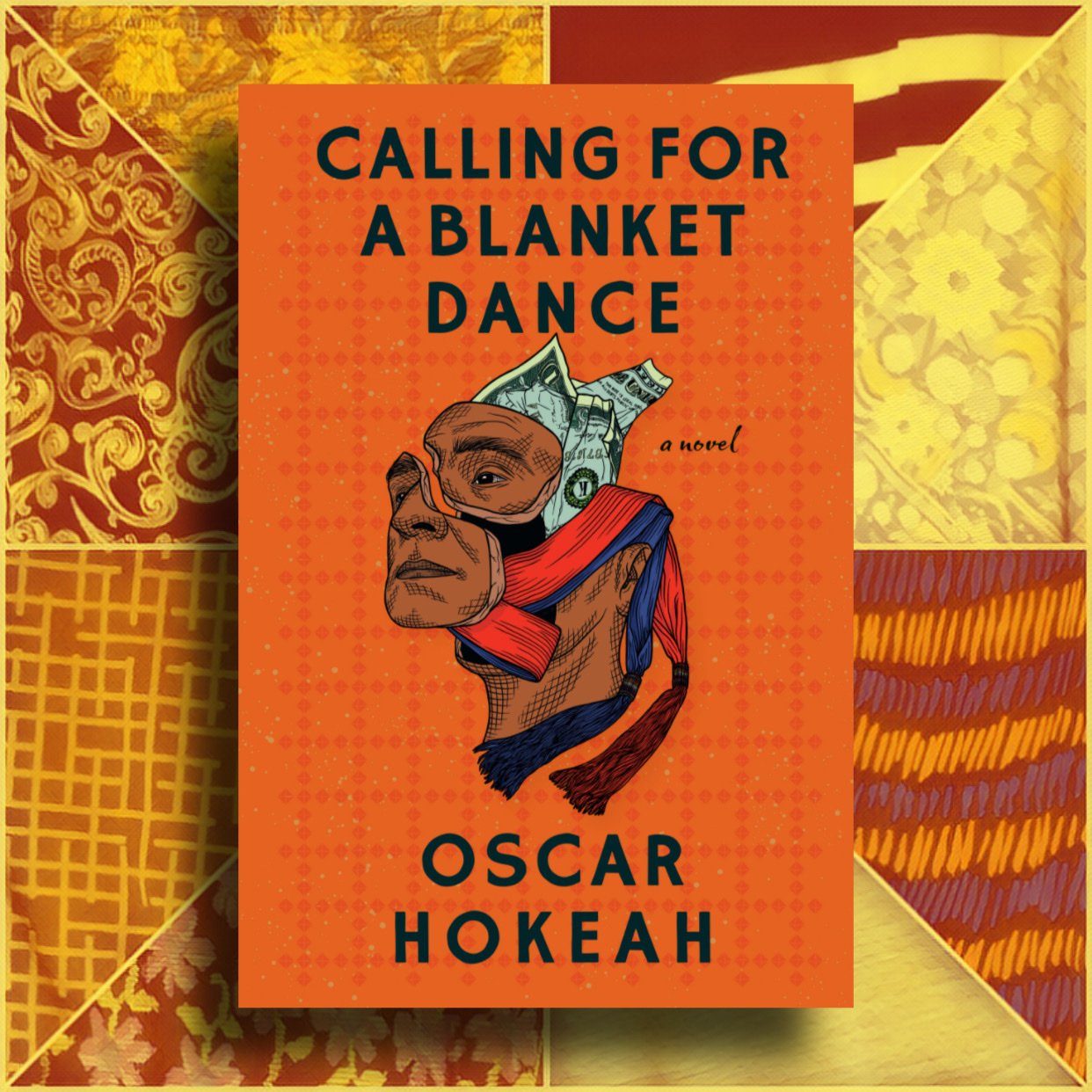

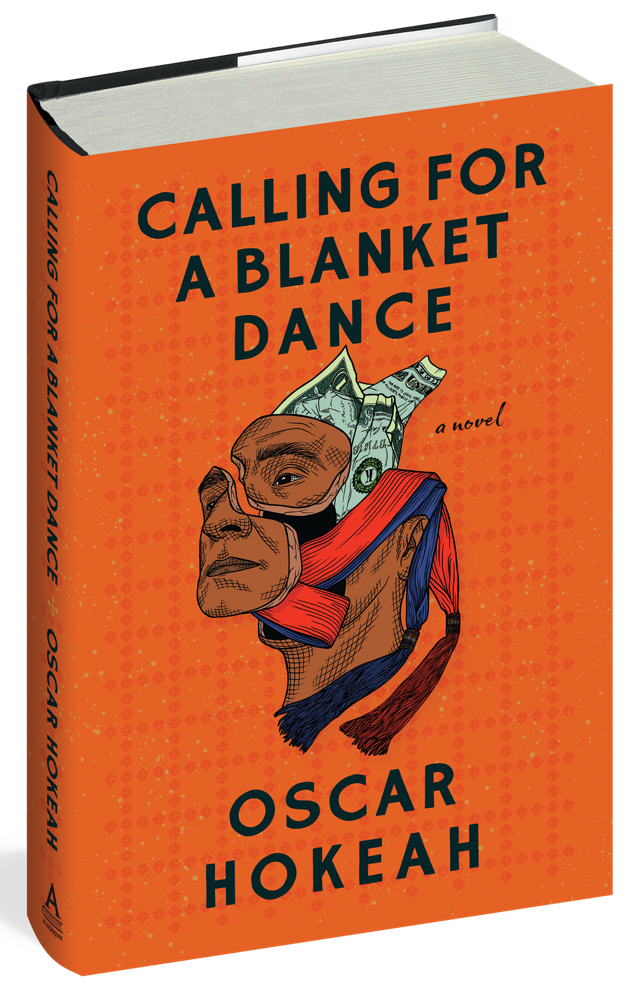

"Stunning" Novel Cover: Symbolic Representations in Post-Modern Art Forms

There are two questions I love most when it comes to talking about my debut novel. One has to do with the structure, with it's polyvocality laid atop time jumps spanning three decades, and the other has to do with the cover. It's a striking image. An image that conveys perfectly the post-modern fracture experienced by the main character, Ever Geimausaddle, and his resilient trek through the process of decolonization.

There are so many layers to this cover, but before I jump into the nitty gritty I'd like to take a moment to talk about the initial reaction to the image. Covers are designed to do one thing more than anything else: Grab the reader. It's supposed to get a reader's attention so that they'll want to further examine the contents. My hat goes off to Christopher Moisan, who is the Creative Director at Algonquin Books. He did an amazing job creating such a wonderful design. I'll discuss here in a moment about how each layer of the image speaks so clearly to the novel. I wanted to acknowledge first how striking the image is and how perfectly it grabs the eye.

Christopher suggested using the artist who created the image, Christin Apodaca. She had been on his radar for a while and he thought her post-modern style matched perfectly with the post-modern aspects of my brand of literary fiction. She is from El Paso, Texas and representative of Latinx communities. I'm half Mexican, with my father being from Aldama, Chihuahua, Mexico, so it was important to work with Hispanic artists from communities of color. And I can't say enough how important it is to support women artists in a field dominated by men. Christin's murals can be found at different locations in the city of El Paso, TX. You can also discover her art here: http://www.capodaca.com/.

Christopher took the power of Christin's image and enhanced it with deeper symbols. The image itself is ripe with symbolic representation. In black and white alone, the dollar bill and sash sends my mind toward Kiowa and Comanche gourd dances. Those of us who engage in traditional gourd dances know that a crumpled dollar bill dropped at the feet of a dancer signifies a process of honoring. I immediately connected how the main character, Ever Geimausaddle, is trying to live with honor. With the sash coming down, I knew this honor was inextricably tied to his family and his community. Christin did a superb job of picking up on those very important symbols in the novel. I can't even imagine the arduous task of reading someone's novel and then coming up with a visual representation of the novel's theme. Christin did exactly that, and she did so with the exquisite detail of her personal style, which I describe as a post-modern Salvador Dali style. And it matched perfectly with the post-modern structure of the novel.

Then we get the brilliance of Christopher Moisan at work. So how does a Creative Director go from this amazing sketch to a final product that will grab a reader's attention? I asked for the image to be made into color and Christopher was on the same page. I let him know to make the sash half red and half navy blue. These are the colors that Kiowa and Comanche dancers wear. I asked for him to place the red on top to signify that the main character, Ever Geimausaddle, is Kiowa. If it were navy blue on top then it would signify Comanche. While Christopher couldn't make the blue a navy blue because it would've printed too dark on paper and wouldn't have looked blue at all. Moreover, it would've erased all of Christin's beautiful line work. So Christopher went with a royal blue with dark line work. I understood his reasoning. It's not only how the colors come out in a jpeg, but also how it prints on paper. Once he filled the image with color not only did the sash pop but the dollar bill as well.

Now the image was an accurate depiction of what I grew up seeing at the gourd dances. I'm a gourd dancer myself. My family (Hokeah/Tashequah) has organized gourd dances for decades on the Southern Plains of Oklahoma. We're tied into some of the oldest Kiowa and Comanche Societies, such as the Kiowa Tia-Piah, Comanche War Scouts, and Comanche Little Ponies.

So I'll be honest here. I gave Christopher a hard time, or maybe I was just a little picky. I hope I wasn't too much of a pain. I wanted to get the colors right. When the ARCs printed, the image came out a little too artificial, I thought. I asked Christopher if the final book was going to do the same. He assured us that he had immediately contacted the printer and discussed the issue. I felt like a bit of a diva. I didn't want any part of the image to come off as artificial, and Christopher was a saint. I'm extremely grateful to have this opportunity to showcase my writing. I feel very fortunate to be in this position. I hope I wasn't too much of a nag. I felt like I kept asking for tweaks here and there. Subtle requests that may have been too often. But I'm grateful Christopher was willing to hear me out and modify at each stage.

What truly made the image resonate for me was the overall design. Christopher came back with a couple background settings. When I saw that pattern atop the orange, I immediately thought of the main character's grandmother, Lena Stopp. Just to explain the brilliant mind of an amazing Creative Director, let me tell you how deep this image goes. Notice the grid. The subtle squares in the background behind Christin's image. The bold orange background beneath red squared patterns, with those splashes of yellow. It's one of Lena's quilts! Now you're about to say I'm giving away a spoiler. You're asking, "Lena makes quilts in the novel?" She does, but this is divulged in the first chapter. You can read the first chapter via Buzz Books through Publishers Marketplace. So I'm not giving away any spoilers that aren't found in the first chapter.

What makes this so special is how Christopher turned the cover into a representation of a bird. Why is that important? As you read the first chapter, you learn that Lena Stopp makes grandchild quilts. On those quilts, she places images of birds. She does so because her family belongs to the Bird Clan in the Cherokee tribe. She uses the quilts as a way to keep her family connected to each other. I got the idea from my own mother, Virgilene Hokeah. My mother makes grandchild quilts for all her grandchildren. They all have the exact same pattern, but each quilt is made of a different color scheme. It captures her grandchildren's uniqueness and their ties to her, simultaneously. Similarly, Lena Stopp uses bird symbols to represent the Bird Clan so her grandchildren will know they are connected to the Cherokee community.

Understanding how to work with artists is an amazing talent. Christopher was able to take Christin's sketch and read my novel and come up with a way to capture the heart of the main character, Ever Geimausaddle. There's an important detail with Lena's quilts that I'll not be able to mention here. It comes in the final chapter of the novel. I'll have to let you discover that element yourself. But I would like to say is how much thought and care went into this cover. While it certainly does its job of grabbing someone's attention, it also speaks to a team of brilliant minds who think beyond simple surface qualities, who can see concepts behind imagery, and has the capacity to dream big and reach deep into the emotional center of a story.

What it Means to Write Decolonization Literature & Why Native Writers Must Not Be Silenced

The process of decolonization. We hear this a lot, and if you've taken a Native studies class then you've likely thought about this in different aspects of society. So what does this look like in literature? I'd like to take a close look at decolonization and talk about the importance of allowing people of color to bear witness on the page, to show readers what it's like to live through sometimes brutal circumstances, and to highlight the dangers of silencing people of color in a Neo-colonial program to whitewash our experiences.

"You can't miss-experience," was a phrase I often heard in the Indigenous Liberal Studies Program (ILS) at the Institute of American Indian Arts. I minored in ILS with a BFA in Creative Writing. Because of my educational background, I'm experienced in examining the intersections between literature and decolonization. Being a literary fiction writer myself, I'm hyper aware of how I execute these dynamics on the page.

When I wrote an entire chapter of my Master's thesis at the University of Oklahoma on N. Scott Momaday's Pulitzer Prize winning novel, House Made of Dawn, I did so with the lens of decolonization--in how the process serves characters in Native stories. Where Momaday writes his main character, Abel, being viciously attacked on the streets of Los Angles by corrupt police, it was an important lesson for me as a Native writer. Here was this explicit scene of male on male violence, and to top it off it was government instituted violence. The scene powerfully shows the residuals of colonization and its effects on Indigenous peoples.

The scene above reminded me of something that happened in my own childhood. In fact, this is one of my earliest memories. I was around three years old. My parents were driving us back from Aldama, Chihuahua, Mexico and heading toward Oklahoma in the United States. We were stopped by Mexican police in a remote area of Chihuahua just south of the Texas border. What happened next would stay in my memory for the next four decades. I'm 46 years old now and can still remember it in vivid detail. Both my mother and father were harassed and extorted by the corrupt police. In the end, my mother would be the ultimate victim in a horrendous situation I don't care to relive now.

Fast forward four decades. I'm working on my debut novel, which has strong themes of hyper masculine constructs. My memory of the above situation coupled with my influence from Momaday inspires the first chapter in the debut. I'm not going to give away any deep spoilers. The first chapter of the novel is available to read through Buzz Books via Publishers Marketplace. I needed to capture a real life moment of Neo-colonial violence--especially one executed from a government institution. Why?

The crux of the novel has the main character, Ever Geimausaddle, seeking to overcome a building aggression. I didn't want to give readers a history lesson on colonial violence in America (that had already been done), but I wanted to give readers a strong sense of how colonization continues to disrupt and fracture Native communities. I was also interested in extending or stretching out our perception of Indigenous communities to include all of Latin America. So my memory of my parents being targeted by Mexican police fit the situation perfectly.

So I did what I always do with my writing, I take a real life experience and modify it--I make it fiction. In the version I used in my debut novel, I made the main character's father, Everardo Francisco Carrillo-Chavez, the victim to corrupt police. Very much in the same way N. Scott Momaday uses it in his novel, House Made of Dawn. Here was a perfectly executed example of how Natives are targeted by police, and an example of continuing trauma Natives must heal from, aka decolonization.

How does the main character factor into all this? Ever Geimausaddle is present during the attack. He's an infant--much in the same way I was only three years old when I witnessed what happened to my mother--and the main character is forever affected by the incident. I'm not giving away any spoilers here. This is the first bite. This scene leads the reader deeper into the crux of the novel, where we must find out if Ever will find his way out of a cycle of violence. If so, who will guide him? And what will it look like from an Indigenous lens?

Often I think about situations on the border, and how it can be a corridor of terror for families. One event that sticks in my mind is when Óscar Alberto Martínez Ramírez drowned alongside his two year old daughter, Angie Valeria, while trying to get into the U.S. via the Rio Grande River. At the time it happened, my own daughter, Hadley, was two years old. I imagined the panic and desperation. And saw myself and my own daughter in those photos. While it was hard to look at the photos of Oscar and Angie, it was important for people to witness the atrocity for themselves.

“I can still see the butchered women and children lying heaped and scattered all along the crooked gulch as plain as when I saw them with eyes still young. And I can see that something else died there in the bloody mud, and was buried in the blizzard. A people’s dream died there. It was a beautiful dream . . . the nation’s hoop is broken and scattered.” ― Black Elk

Because violence is a very real experience for people of color, I can't express enough the importance to bear witness on the page. Especially for us literary fiction writers, who are tasked to be advocates for change. There is a real danger in silencing artists, or the attempt by many who've never had to experience violence in the first place. What would've happened if we asked photographers to not take pictures of the Native American Holocaust? When N. Scott Momaday writes about police violence over a half century ago, and a Native writer like myself shows readers the continuation of this government sanctioned violence today, we must remember that Natives have been enduring brutality for hundreds of years.

Vernacular, Agency, & Intersectionality of Language Transformation

Growing up in households where words and phrases in both Kiowa and Cherokee were spoken and mixed with English, it gave me a unique understanding of language. As my family spoke, someone could be both skaw-stee and mon'sape. Skaw-stee is a Cherokee word that means "stuck up," and mon'sape is a Kiowa word that means "trouble maker." Mix these words with other phrases and Indigenized English words like gaa which is the Native version of "golly," and all of a sudden language becomes a playground of agency. Where this Kiowa/Cherokee/Mexican boy had a canvas of words to create a beautiful new symmetry.

When I arrived at the University of Oklahoma for the Master's program in English, I had already written one of my earliest pieces where Kiowa and Cherokee communities intersected. I became even more fascinated by colloquial vernacular and the waves it could create in literature. It made sense to me. Of course community members had the freedom to use language in a way that made sense to them. Each community, whether tribal or not, had its own terms and sayings and accents and ways of engaging, and every community had the freedom to make of language what it wanted.

While I was learning to be a grammarian, I also learned how to break those rules exquisitely on the page. For me, it was an act of rebellion. I was going to exercise my agency and use language the way it was used in the households where I grew up and had access to. As a child, I could be at a traditional Gourd Dance and hear Kiowa and Comanche and then later in the same summer be at traditional Stomp Dances and hear Cherokee or Creek. Then there were times when I'd be with my cousins in Aldama, Chihuahua, Mexico and hear streams of Spanish. I shifted between these cultures fluidly, and all these languages were normalized as they landed on my ear. I didn't think it odd or unique. This was my life and it was just the way things were.

Fast forward a few decades and I'm in a classroom at the Institute of American Indian Arts in Santa Fe, New Mexico. I'm buying into the doctrine of "literary fiction," where we bear witness to our experiences, where we bleed on the page, where we tell on ourselves before we tell on anyone else. And as I'm writing as catharsis, seeking to heal deep traumas from childhood, I'm also aiming to capture my communities and my families the way I had truly experienced them. Not some generic version of Native identity that makes white people feel safe enough to consider us "model minorities," in some type of sad display of pitiful. But Natives who were sometimes mean and vicious and were amazingly cruel heroes. Blur the lines between hero and villain--make characters so human that readers think they're real.

And in all that, I had to be honest about the intersectionality of language and how language itself is "real" and "living." I knew I wasn't only going to capture character with genuine authenticity, but I needed language to lay on the page the way it lays on the lips of children--with direct honesty. This is what I heard. This is what I said. This is the way we were--and still remain. So when you engage my debut novel be prepared for language and rhythm to disrupt your senses. You think you know Native peoples, but you only know a Native people, and are about to learn what it means to be Indigenous in a Neo-modern intertribal world, where Turtle Island is the only map to show you the way.

Intro to Literary Fiction: A Native American Writer's Reasoning Toward Episodic Novel Writing & Unfamiliar Terms in Familiar Terrain

"What do you write?" Have you heard that question before? For literary writers this question is like a grain of dirt on the ass cheek of a wild hog running through the brush in the Ozark Hills. Every time I go to answer the question I know what's going to follow. It's going to be another question, with a quizzical expression on the questioner's face, asking me, "What's literary fiction?"

I wish I could say, "Literary Fiction," and folks would go, "Okay, that's cool," and then we could both go our separate ways. But that's never happened, and likely never will. In recent years, I've heard the term "adult fiction" being used more often. Maybe it's because we get less confusion and less hassle so we've started to lean on it. It's kinda like when I call to-go from a restaurant and the person on the other end of the phone doesn't hear my name right. I'll say, "Oscar" and they'll say back, "Austin?" I'll do this three times and then give up, saying, "Yes, Austin." At some point, literary writers get tired of trying to explain ourselves.

I've also started to name writers and for the most part I'll say Louise Erdrich, but I've also said Toni Morrison's name, to give folks a reference point--in search of someone they may have heard of. Typically, I name writers who have won the Pulitzer Prize or the Nobel. But the average person on the street doesn't follow those lists so often I'm left without a quick reference.

I've searched on the internet. There's "serious fiction," but I think that's more confusing than literary fiction. Adult fiction makes sense. It's a little more to the point, but most genres could be considered adult fiction. While literary fiction fills the shelves in bookstores for some reason there is little to no clarity on the genre. How can such a popular form of fiction have such a vague understanding?

"However, we should not be judged by our lowest common denominators. And also you should not fall prey to the fallacious thinking that literary fiction is literary and all other genres are genre. Literary fiction is a genre, and I will fight to the death anyone who denies this very self-evident truth." --Patrick Rothfuss

Then there's the response I get from writers of other genres. Some folks think literary fiction writers are stuck up and look down on genre, which couldn't be further from the truth. I love genre fiction and read across several genres like horror, fantasy, and noir. I think literary writers tend to be more serious in our personalities and that might come off as being disinterested. I can only speak for myself so I'll say that I am a serious person and I tend to be drawn to more serious issues. There's a part of me that feels obligated to attempt to fix societal issues, like I need to do my part to make life better for people of color. But in no way do I think genre fiction is less than literary fiction. If not for genre fiction I wouldn't have fallen in love with writing in the first place.

So I've come up with a description of literary fiction. Just to appease myself and my frustration in the pursuit of an explanation. Here it is: "An introspective study of the human condition that explores sociopolitical issues. More serious than genre fiction, it purposefully blurs the lines between hero and villain to focus on character driven plot. In addition, it seeks to disrupt formulaic writing."

It's long. I can't say this to someone on the street. But it knocks the dirt off the wild hog's ass, so I'm gonna keep it. I think people need to understand what they're getting into before they start reading a novel. My debut, CALLING FOR A BLANKET DANCE, is about Native communities, culture, and identity, but it's also about how Indigenous families confront toxic behavior. It's about the conflict between Indigenous matriarchy and Western patriarchy. What happens when these two ideologies clash? The main character, Ever Geimausaddle, becomes a battle ground. He's caught between two contending forces and he must make a choice. And if he does transform, what will it look like? The only way I could do this story justice was to wrap it in the genre I hold dear: Literary Fiction.

Native Voices for Native Audiobook: Recording Chapters in CALLING FOR A BLANKET DANCE

I can't tell you how grateful I am to be able to read for my debut novel. Many writers don't get the opportunity to record for their own audiobooks. Because my novel is polyvocal and comes from the heart of tribally specific communities, Kiowa and Cherokee, I was more than happy when Algonquin Books asked me to read for the male characters in my debut. Moreover, they hired a Native actress to read for the women characters: Rainy Fields.

You might know Rainy Fields from her work with Terese Marie Mailhot's debut, HEART BERRIES. Rainy is an enrolled tribal member, Muscogee Creek/Cherokee, and born in Claremore, Oklahoma. I was elated when she signed on to read for the audiobook. She is an experienced Native actress and well-versed in recording audiobooks.

I on the other hand was not so well versed. This was my first time recording anything--much less half a novel. It was fun though. I learned a lot about the world of voice recording. Honestly, I hope I get the chance to do this again. I feel like I caught on quickly. I needed direction at the beginning and the more I recorded the more I caught onto moments when I'd miss a word or add one in.

I was especially interested in capturing the Kiowa and Cherokee inflections in the voices. I've said this before on previous blog posts. While both Kiowa and Cherokee people have Oklahoman accents, there are subtle differences between the two. Kiowa people can almost transform English into a Kiowa-sounding language, whereas Cherokees have a stronger twang to our inflections--a little more singsongy. It was fun being able to move between those subtle dynamics in the two tribal communities I hold so dear.

I have to give a big wado to Blue House Media for coordinating with Hachette Audio/Algonquin Books for these recording sessions. Joel was great, kind, and generous. He quickly took care of any issues and was pleasant company. He made the experience fun and exciting. And of course where would I be without Cameron Potts of John Marshall Media, who directed the entire recording and was an amazing coach, and Laura Essex from Hachette Audio, who oversaw the entire production and gave amazing feedback. I'm feeling very lucky to be a part of such a wonderful and supportive team.

As a Native writer, I was excited to be able to have Native people doing the voices for my audiobook. I'm very grateful Algonquin Books was considerate of this very important cultural dynamic. I'm excited how there are different aspects to the production of the debut novel of which have connected to the three intersecting cultures in my life, Kiowa, Cherokee, and Mexican. While there's always going to be detractors and naysayers (those cliched crabs-in-a-barrel), I'm proud to have been able to connect with artists from both Native and Mexican communities.

The Revival of Juxtaposition & the Reveal of Thematics

When we pick up any literary novel we must commit to being an active reader. We can be entertained by the surface plot and the triangulation between characters, certainly. But the purpose of literary fiction is to dive deeper into the text and search for symbols. Not only the symbols that comprise a larger thematic in a storyline, but, more importantly, the symbols that shape the really real world we walk through every day.

We can all make a case for engaging in a storyline passively. Sometimes we need to veg out on our favorite television show after a long day of hard work. Or we can reread one of our favorite books from one of our favorite authors. We know what's coming. It's not going to surprise us, and in fact we're looking for those predictable forms of entertainment as a way to escape our every day grind.

Then there comes those who are students of the game. Sometimes life gets a little too predictable and we need nourishment and intellectual stimulation. This is where literary fiction shines. Writers like Louise Erdrich, Toni Morrison, Alice Munro, and the like can entice us with intriguing worlds through beautiful sentences. And the deeper we look at their work, searching for the images and characters that represent something greater, we can discover insights into the human condition that make us into better people. Our empathy skills increase and we can better navigate social situations, with the hopes of creating a more just world.

When I think back on some of my favorite literary novels, I'm always remembering characters weighed against other characters, like in Louise Erdrich's novel The Roundhouse, where the treatment of Geraldine Coutts becomes even more profound as we learn more about Sonja. Equally, how Gabriel Garcia Marquez's novel One Hundred Years of Solitude exposes a new layer to humanity with each generation of the Buendia family. So when we exercise the power of juxtaposition, the multiple layers expose a greater truth. And often this truth gives us a hard look in the mirror, forcing us to self examine our own contributions to societal ills.

Ultimately, the reason I'm discussing juxtaposition today has to do with dynamics in my own writing. I'm brainstorming book 5 right now and searching for more details as the story concept floats around in the back of my mind. Also, much of my fiction, which is literary fiction, is developed through a variety of devices--one being juxtaposition--and I can't help but think of how each character weighs against the others.

"I'm always trying to find 'connections' between things. That art is the juxtaposition of a lot of things that seem unrelated but add up to something recognizable." - Pat Metheny

This dynamic plays out with much intentionality in my debut novel, Calling for a Blanket Dance. The novel is told by 12 different narrators with the purpose of juxtaposing each. Moreover, how each narrator compares and contrasts to the main character, Ever Geimausaddle. In fact, the thematics of the novel can only be discovered by juxtaposition. So much so, in the final critical moment of the novel, the reader must ask themselves: how would each of the previous 11 narrators act in this moment? Would they have done what Ever did in the final scene? I'm keeping these questions ambiguous right now because the novel doesn't release until July 26, 2022. I'll do my best here to not give away any spoilers. But it's the power of juxtaposition that offers the novel its greatest impact.

A longtime effort of mine, which is also showcased in the debut, is to disrupt the perception of Native Americans being a single homogenous group. Each tribe has beautiful differences, and we are drawn together under a shared colonial history. It's the power of juxtaposition that gives me the ability to show this tribal diversity on the page. The main character, like myself, belongs to two different tribes: Kiowa and Cherokee. I'm able to compare and contrast Cherokee communities with Kiowa communities. The first chapter is narrated by Lena Stopp, who is Cherokee, and then the second chapter is narrated by Vincent Geimausaddle, who is Kiowa. Each chapter moves back and forth between Kiowa and Cherokee community members so the reader can see those beautiful differences. Oklahoma has 39 different tribes and those of us who grew up here know these differences well, but if you're not consistently in our circles it can be difficult to distinguish. Juxtaposition gives me the opportunity to show readers a side of the Native American world they may have not yet considered.

“Creativity is that marvelous capacity to grasp mutually distinct realities and draw a spark from their juxtaposition.” ― Max Ernst

I only have time here to touch the surface of how juxtaposition plays out in my debut. As you come to know the characters, you'll see why Sissy narrates Lonnie's story and then how Lonnie and Leander compare and contrast. Moreover, how Ever Geimausaddle compares to his grandfather, Vincent. Does Ever pick up where Vincent left off? What does Ever do differently? How does this choice alter Ever's life? I could go on and on. The debut is so rich with juxtaposition, like Opbee and Lena, Turtle and Lila, Quinton and Ever (Sun Boy Split in Half). And it's only enhanced by the cultural elements throughout the novel. There is so much to discuss that I could go on and on for hours if not pages, and I hope you pick up a copy of Calling for a Blanket Dance so we can talk about these amazing details. I'm looking forward to the rich discussions this novel will generate.

Lately, I've found myself thinking a lot about the power of juxtaposition and how much we need to exercise this muscle as readers. It gives us the opportunity to view another person's hardships with empathy, but it also creates a much richer existence, where our quality of life is enhanced by a simple task: compare and contrast. And when we do so with purpose and intent, we can better see the world through someone else's eyes.

(Images were borrowed from Flickr)

Highly Anticipated Debut Novel in 2022 from Native American Author

So I know it's not cool to say "own voice writer" anymore these days, but we have to give credit to the Native writers writing from inside our own tribal communities. It doesn't happen as often as you might think. And you know what happens even less? When a debut Native writer from inside his tribally specific and historically targeted community gets a little recognition.

It's not easy writing about yourself. It's awkward. It can come off as egotistical. The shameless self promotion. I apologize, truly, for any of those vibes that may come out of this post. Honestly, it can be rough waters out there for any debut author, and we try to find small ways to get our novels into the hands of would-be fans.

Plus, we work years and years, toiling over words and living deep inside our imaginations to bring readers a vivid, entertaining, and sometimes eyeopening story. My debut novel, CALLING FOR A BLANKET DANCE, has been 14 years in the making. The earliest chapter was written back in 2008, and the debut will hit shelves on July 26, 2022. That's a long journey. We work hard on these projects and are eager to find readers to entertain.

Then we have good news to share and want to tell anyone who's willing to listen. That's part of the reason I'm writing this post. The debut has been honored with "most anticipated" and "highly anticipated" or "key debut" and I'm excited to share the wonderful news. Check out the list below:

- Library Journal (Key Literary Debut 2022)

- Goodreads (Highly Anticipated Debut 2022)

- Buzz Books by Publishers Lunch (Buzz Worthy Book 2022)

- Book Page (Most Anticipated Fiction 2022)

- Bookshop (Most Anticipated Book 2022)

- Bookish by NetGalley (Highly Anticipated Book 2022)

- Changing Hands Bookstore (Most Anticipated Book 2022)

Now if you'll let me share with you a description of the novel:

A moving and deeply engaging debut novel about a young Native American man finding strength in his familial identity, from a stellar new voice in fiction.

Told in a series of voices, Calling for a Blanket Dance takes us into the life of Ever Geimausaddle through the multigenerational perspectives of his family as they face myriad obstacles. His father’s injury at the hands of corrupt police, his mother's struggle to hold on to her job and care for her husband, the constant resettlement of the family, and the legacy of centuries of injustice all intensify Ever’s bottled-up rage. Meanwhile, all of Ever’s relatives have ideas about who he is and who he should be. His Cherokee grandmother urges the family to move across Oklahoma to find security; his grandfather hopes to reunite him with his heritage through traditional gourd dances; his Kiowa cousin reminds him that he’s connected to an ancestral past. And once an adult, Ever must take the strength given to him by his relatives to save not only himself but also the next generation of family.

How will this young man visualize a place for himself when the world hasn’t given him a place to start with? Honest, heartbreaking, and ultimately uplifting, Calling for a Blanket Dance is the story of how Ever Geimausaddle found his way to home.

If my debut sounds like something you'd like to check out, please reach out to your local bookstore and ask them to carry copies of CALLING FOR A BLANKET DANCE. You can also preorder at your favorite online retailer:

- Bookshop

- Barnes & Noble

- Amazon

- Target

- Walmart

- Books-A-Million

- IndieBound

- BulkBookstore

- Indigo (Canada)

To learn more about who I am and where I come from, feel free to peruse my website, read a few blog posts, and check out my social media. I'm most active on Twitter, but I'm trying to find more time on Instagram. I've recently made a TikTok but I'm still learning the ropes (so I apologize if my TikToks are a little crude).

Thank you for hearing out a nothing-little-Native from small-town Oklahoma. I hope you get a chance to read my debut and dive into Ever Geimausaddle's eclectic world. If you have a moment, drop a line in the comments below. I'm always happy to answer any questions and talk shop.

Digesting Fragments as Memories: CALLING FOR A BLANKET DANCE

Let me ask you a simple question: What was a significant event in your life? Moreover, how did it impact you, change you, make you into the person you are? What I like most about this question is how it immediately takes us deep into memory. Suddenly a series of memories flood our minds and we rifle through each to determine which might be the most impactful. Now let me switch it on you. What if I asked each of your relatives about the most significant event in your life?

Suddenly, we might have multiple stories. Your grandmother might tell a different story than your grandfather. What about your parents? Your spouse? Your siblings? Your cousins, aunts, uncles? Now we have an entire chorus, a symphony if you will. And in this symphony the music is an ensemble of memory.

“It's enough for me to be sure that you and I exist at this moment.” ― Gabriel García Márquez

One could argue we primarily exist by memory. The memories others have of us. The memories we carry about ourselves. Each moment we share in real time can only be processed in memory. Does this mean there is no here and now? Is memory the only form of existence?

Before I carry on too much longer with all these questions let me say here that my debut novel, CALLING FOR A BLANKET DANCE, allows readers to consider these very questions. The structure of the novel is told by 12 narrators. The main character is Ever Geimausaddle. Each chapter is told by a different family member. We start with his grandmother, Lena, and then move onto his grandfather, Vincent, followed by his uncle, Hayes, and so on and so forth, going through aunties, uncles, cousins, and his sister. Then in the final chapter we hear from Ever himself.

Where the aspect of memory comes into play is the time span between each chapter. Lena tells us a story about when Ever was an infant, while Vincent tells us a story about when his grandson was five years old. Then his uncle follows with one from when Ever was 10 years old. The chapters hop three to five years at a time, and does so into his adulthood, ending when Ever is in his early 30s.

Why would I do this? What's the purpose of spanning so much time between each chapter?

The simple answer: memory. How does our memory work? When I ask you about a significant event, your mind searches for moments in time. It doesn't run in a linear fashion without any breaks from the moment you were born until this very moment. So this begs a bigger question: Do our lives only exist in fragments? If we are simply constructs of memory, how much say do we have in the constructs of our own identity? To my mother, I'm a son, but to my best friend, I'm a brother. In order to truly see into the depths of who we truly are, don't we depend on the memories of others?

“He was still too young to know that the heart's memory eliminates the bad and magnifies the good, and that thanks to this artifice we manage to endure the burden of the past.” ― Gabriel García Márquez

Let the spaces in between each chapter jar you, let them force you into new spaces, let them make you imagine a new version of time--maybe a more honest version of time. Not only will you truly see Ever Geimausaddle as a loving and flawed human being, but you'll forgive yourself for being one too.

“Please — consider me a dream.” ― Franz Kafka

(The image was borrowed from flickr.com)

Mona Susan Power's Praise for Oscar Hokeah's Debut Novel: CALLING FOR A BLANKET DANCE

You have to understand how big of a fanboy I am. When someone asks me for a book recommendation, Power's story collection, ROOFWALKER, is usually the first I name. It captures perfectly the flux between community/reservation life to an urban Native experience. I have a special love for the book because I taught it in my Native Lit class at the Institute of American Indian Arts. This was back in 2013 when the then Head of Creative Writing, Evelina Zuni Lucero, asked me to adjunct for a semester. When I compiled my list of Native fiction to teach, Mona Susan Power's book was at the top.

When my editor, Kathy Pories, of Algonquin Books asked me to reach out to Native authors to request blurbs, I immediately thought, it'd be a dream to have Susan Power's blessing. Then I figured it was far fetched. There was no way Susan Power would be able to read my book. Here I am a nothing little Native writer from nowhere Oklahoma. She's not going to respond to me. But Kathy assured me that writers are more inclined to respond to other writers in these situations. I'm so new to all this, being a debut author, and I'm still learning as I go. I trusted Kathy and thought, okay I'm going to give it a shot in the dark.

Mona Susan Power is most well-known for her own debut novel, THE GRASS DANCER, which was released in 1994. It's described as "the harsh price of unfulfilled longings and the healing power of mystery and hope. Rich with drama and infused with the magic of the everyday, it takes readers on a journey through both past and present—in a tale as resonant and haunting as an ancestor’s memory, and as promising as a child’s dream." Her debut novel is published by Penguin Random House, and won the Ernest Hemingway Foundation Award for First Fiction. The novel received praise from numerous news sources, including The New York Times, Washington Post, and the Chicago Sun. Additionally, Louise Erdrich and Amy Tan gave beautiful blurbs for the novel.

The short story collection I mentioned above, ROOFWALKER, was released in 2002 from Milkweed Editions, and described as "a world in which spirits and the living commingle and Sioux culture and modern life collide with disarming power, humor, and joy. The characters grapple with potent forces of family, history, and belief—forces that at times dare them to do more to feed their identity, and at times simply paralyze them. Rich with women who do things, this book gives voice to characters who make space for contradictions in their lives with varying success and, by extension, live the 'Indian way' to varying degrees." This short story collection resonated powerfully with students in my Native Lit class and I highly recommend instructors to add this one to their lists. Moreover, Louise Erdrich described ROOFWALKER as "A book of wild humor and compassion." I can't sing enough praise for this book. I loved the depth of the characters and how each story stacked atop each other like bricks, capturing an emotionally rich experience of a Native community.

Her latest novel, SACRED WILDERNESS, was released in 2014 by Michigan State University Press. It's described as "A Clan Mother story for the twenty-first century, Sacred Wilderness explores the lives of four women of different eras and backgrounds who come together to restore foundation to a mixed-up, mixed-blood woman—a woman who had been living the American dream, and found it a great maw of emptiness. These Clan Mothers may be wisdom-keepers, but they are anything but stern and aloof—they are women of joy and grief, risking their hearts and sometimes their lives for those they love. The novel swirls through time, from present-day Minnesota to the Mohawk territory of the 1620s, to the ancient biblical world, brought to life by an indigenous woman who would come to be known as the Virgin Mary. The Clan Mothers reveal secrets, the insights of prophecy, and stories that are by turns comic, so painful they can break your heart, and perhaps even powerful enough to save the world. In lyrical, lushly imagined prose, Sacred Wilderness is a novel of unprecedented necessity."

I was excited to cross one of her Facebook posts the other day, where she announced she had recently acquired a literary agent for a NEW NOVEL! Yes! I'm very excited for her next novel, A COUNCIL OF DOLLS, to find a home with a publisher. I'll be placing it on pre order ASAP! From what I understand, it appears to be in early stages with an agent, but I'll be keeping a look out for this novel in the future--hopefully near future.

Needless to say, after giving it a shot in the dark, I unexpectedly received a response from Mona. I couldn't believe it. I quickly clicked on the popup for Facebook Messenger and her message showed on my iPhone's screen. I read the words "thank you for teaching my work" and "congratulations on finding a wonderful publisher," and I half expected her to be too busy and not be able to read my debut novel. Then I read the words "I'd be honored to have an early read of your forthcoming work." I thought, what? So I read the words again, "I'd be honored to have an early read of your forthcoming work." I couldn't believe it. She said, "Yes." Mona Susan Power said, "Yes."

I clicked over to my email and typed as fast as my fat thumbs would allow, sending Kathy Pories and my agent, Allie Levick, the good news. They both emailed back quickly with excitement. We were all delighted to have Mona give the novel a chance.

Then came the waiting. Oh, the waiting. It's more the wondering. Maybe the not knowing, but hoping. I'm such a fanboy. I called a close friend and told her, "Susan Power is reading MY book." I was excited and nervous to hear her thoughts. What would she think of the main character, Ever Geimausaddle? How will she respond to the tri cultural intersections? Did I capture Oklahoma's intertribal dynamics well? If there is ever anyone you want to impress, it's someone you've admired for so long.

Then a few weeks passed and she responded. Again, I saw the notification for Facebook Messenger and I immediately clicked it as soon as it hit my screen. Then I couldn't believe what I read. It was filled with such wonderful praise. I just couldn't believe she enjoyed my book. I'm excited to share with you Mona Susan Power's praise for my debut novel:

"CALLING FOR A BLANKET DANCE is a stunning novel I couldn't stop reading! Oscar Hokeah writes from deep inside the heart of his communities, bringing life to generations of voices who became so real to me they felt like relatives. The reader can't help but invest in each character as they navigate bitter challenges, sometimes surprising themselves with their strength, their ability to survive and love. Hokeah's prose gorgeously weaves authentic local vernacular with the lyrical notes of hard-won insight. This novel belongs on every recommended booklist for fans of literary fiction!"

My debut novel will release next year: July 26, 2022. Right now it's available for pre order at most online retailers, but I do like to promote Bookshop because it gives a portion of the money to a local book store in your area.

I'm so very grateful Power was willing to give my novel a chance. And super delighted for her wonderful praise. I'm still floored by her generosity in helping a new Native writer come on the scene. It's not easy. Especially as you're learning as you go. I feel very humbled by all this. I really can't express enough how grateful I am.

The heart of the novel has to do with family, naw thep’thay’gaw, and how families show up for each other. The title of the novel comes from an important ritual in powwow culture. When we call for a blanket dance, in essence what we’re doing is asking for the community to step up and help out someone in need. The main character, Ever Geimausaddle, has a host of family members willing to do just that, willing to hear the call, step up to the edges of the blanket, and offer a piece of themselves for his greater healing.

The structure of the novel is told in 12 chapter/narrator fashion, and we hear from different family members–grandparents, aunties, uncles, cousins, and then in the last chapter Ever Geimausaddle speaks for himself. Ever’s identity becomes shaped by Kiowa, Cherokee, and Mexican relatives, and the crux of the novel has his family concerned for his changing identity as a man. His Cherokee grandmother, Lena Stopp, fears the brutal trauma he experiences as an infant will forever leave him “witched,” while his Kiowa grandfather, Vincent Geimausaddle, fights to change Ever’s fate with his dying breath. Moreover, his Mexican American cousin, Araceli Chavez, is the conduit for deep familial healing. So family member after family member step up to the edges of the blanket to offer a piece of themselves. But will this be enough?

As Ever grows into adulthood, readers will get to explore large and unique themes situated in tribally specific values, like tribal matriarchy, communal ideology, and collective identities. Furthermore, readers will follow Ever Geimausaddle through the ups and downs of living an intertribal and multicultural life in Oklahoma, offering a slice of America very few know about.

Native Heroes for Character Building: Issues with Villains and Victims in Storytelling

"Did you hear about Kaleb Nowater? Maybe his name was Kevin. I'm not sure, but it was a K name for certain. Come to find out, he was sexually assaulted by a worker at that children's group home. By whom? It was ol' what's his face. I forget, but he likes to surround himself with those wannabe artists. Anyway, they fired him because they caught him sleeping during overnight shifts in that poor boy's room. Awful. And imagine all those artists who just look the other way. I wonder if they know. More so, I wonder if they care more about their reputation than a child getting harmed. Just makes me sick to my stomach thinking about it. Who makes sexual advances on a teenage boy with emotional and psychological issues?"

So the above paragraph does a lot of interesting things. I'll not breakdown all the elements here. What I'd like to focus on is the dynamic between "the child with the K name" and "ol' what's his face." The victim and the villain. Immediately, we get caught up in the drama of the situation. It's intense. Someone is manipulating vulnerable teenage boys for sex. Our protective senses kick in and it makes us want to reach into the story to protect the victim. So this is perfect. This is exactly what writers want to do with a narrative.

But is this sustainable? Can we go on for page after page with this victim and villain pattern? Now what if I said the pedophile was Cherokee and the victim was Creek? Now we are instantly shinning a spotlight onto entire communities of color. And communities of color from the smallest minority in America. We can't overlook this dynamic because the stories we release into the world have real implications. People respond. People are affected. Lives can be altered. Legacy's can be ruined. And in an instant.

For some reason, I keep crossing Native characters being perpetuated as extreme victims or extreme villains. Now we're immediately drawn to the language in the first paragraph because it resembles how we talk amongst each other in our own communities. This is how we protect our children. Unfortunately, convicting someone of a sexual crime on a child is incredibly hard to do. So what do we as heroes do? We protect our families. We tell each other who is doing what so that families will keep their children away from predators, so employers will know who not to hire. With the initial language above, our protective factors jump in and our interest heightens.

Not only does the narrative implicate the villain, but it also implicates an entire group of people. A cult, if you will. It alludes to a cover up, or at minimum people looking the other way. And if we place this in the context of Cherokee people, the villainy suddenly paints the entire community in a certain light. It makes us ALL look bad. And keep in mind that we have some of the highest disparity rates in the U.S. The last thing we need is to have an even worse disparaging look as Native people.

As Native artists, we have to consider these variables. What is this going to look like? Is this an accurate portrayal of Native people? Ultimately, what image will Native people have?

Now, this doesn't say we don't write about serious issues. On the contrary. We, as Native artists, have an obligation to capture the worst, like underground pedophiles, so as to create topics of discussion. This goes back to keeping our communities safe. My point here is that instead of focusing on the victim and villain, we should be looking at the heroes in the situation.

Let's consider if "the child with a K name" comes back as an adult and confronts his abuser. Now we've turned the victim into a hero. What if we refocused the narrative to spotlight the victim getting his revenge? Then not only do we get a chance to see multiple sides to the character, but Native communities of color are seen as the heroes, and having the ability to tackle serious issues ourselves. Moving away from needing a white savior to rescue us. So in the spirit of empowerment let's rephrase the first paragraph:

"Did you hear about Kaleb Nowater? Maybe his name was Kevin. I'm not sure, but it was a K name for certain. Come to find out, he went after a former worker at that children's home. Who did he go after? It was ol' what's his face. I forget, but he likes to surround himself with those wannabe artists. Anyway, it turns out Kaleb was a foster child in that group home and he was sexually assaulted by that worker. It was during overnight shifts in Kaleb's room. Awful. But Kaleb came back and told all those artists about his abuser. Do you know what they did? Well, I'm a good Christian so I can't say, but I'll tell you this: That pedophile checked himself into a hospital for "mental health" issues. But we all know what that means, right? So glad Kaleb finally had his day."

Now that's a story worth telling!

(Image above borrowed from wikipedia)

Cherokee Actor: Kholan Studie Starring in Short Film "The Dark Valley"

You have to respect an artist for taking bold steps. That's what we do. We're here to capture the harsh realities and interpret those realities for purposes of entertainment, as well as processing tools for deep intellectual thinking. When I cross artists who are willing to truly reach deep inside themselves to find an honest portrayal of the world, I immediately recognize game. These are the real ones. The ones envied by the weak, the unwilling, the carcasses of outdated memories.